Norwegian Wood is one of the greatest novels of the 20th century and a goldmine of writing advice. If you’re serious about becoming a better writer, you should consider each book you read to be a schooling in the craft of language, character, and story. Today our teacher is Haruki Murakami and our textbook is Norwegian Wood.

Stick on some Beatles, stretch out with a beer, and grab your copy of the book. Class is now in session.

Warning: Spoilers Ahead. If you haven’t read Norwegian Wood, turn back now.

Norwegian Wood was published in 1987 and was the work that propelled Murakami into the literary limelight. The book sold over 4 million copies when it was first published, which resulted in a lot of unwanted attention for Murakami, prompting him to move back to Europe (where the book was originally written).

The story is told from the point of view of an older man looking back over his life at university. It’s a deeply reflective coming-of-age story that sees Toru Watanabe try to understand his relationship with the girlfriend (Naoko) of his best friend (Kisuki) years after he committed suicide.

No matter where you are in life, Norwegian Wood is bound to form a strong impression upon you. The book’s themes of love, loss, and sex will stir up a storm inside you. And if you’re a writer, you can learn a lot about the craft by consciously studying how Murakami moulds his narrative. So let’s dive in and see just a few reasons why Norwegian Wood is so great.

10 Things Writers Can Learn From Haruki Murakami’s Norwegian Wood

1. Sensuality – Erotica Writers Take Note!

I may or may not have spent some of my self-publishing career in the erotica circuit. And in that time I devoured all of the genre’s classics, bestsellers, and lesser-known gems. I found a few diamonds in the rough but, for the most part, erotica (especially the stuff climbing the Amazon charts today) made me supremely uncomfortable.

I’m not the only one that finds most of the books cringe-inducing. Just scroll through the reviews of some of the top sellers (most of which will disappear into oblivion within a fortnight) and you’ll see a common round of complaints: too much detail, too wooden characters, not enough build-up, and not enough believability.

Writing good sex is not like following an Ikea DIY flatpack instruction panel. Insert rod A into fixture B and screw until you hear a moist popping sound = GROSS.

Erotica readers do not just want a play-by-play of every minute detail. If they wanted that, they could find tons of that shit on the internet (seriously, open up a tab right now… I’ll wait) rather than fork over eight bucks of hard-earned money on a book.

When it comes to writing effective erotica….

- What’s unsaid is more important than what is said. It’s the same in horror where you don’t see the bad guy until the end. Let the reader’s imagination take over. Everyone’s fantasy is different.

- You need characters that have real emotions. It can be love. It can be hate. It can be jealousy, possessiveness, fear, boredom, disgust. But it can’t just be sex.

- You need to have a build-up that is believable. Seriously, female protagonists shouldn’t go from straight-laced Christian girls to nymphomaniacs overnight. That’s a dirty deus ex-machina that serves only to heap up a big serving of forgettable and creepy description.

You can learn how to do all of this stuff by reading Murakami’s Norwegian Wood. Sensuality, love, and sex are major themes and Murakami doesn’t ruin those themes by just throwing them down on the page without paying careful attention to atmosphere and character first.

I won’t quote any of the erotic scenes from Norwegian Wood here because there’s too many to choose from. But suffice it to say, Murakami is able to make a hand job in a meadow feel more profound than 50 pages of bestseller frame-by-frame hardcore ramming.

He does this by focusing on character. He focuses on real issues that real people deal with every day. Then when the scene comes, he introduces it and steps back.

Quick Reading List For Erotica Writers: Study Haruki Murakami, Anne Rice, Kazuo Ishiguro, Jane Austen, and a bunch of Harlequin Romance classics.

2. Natsukashii – Nostalgia Is Hard (But Important) To Master

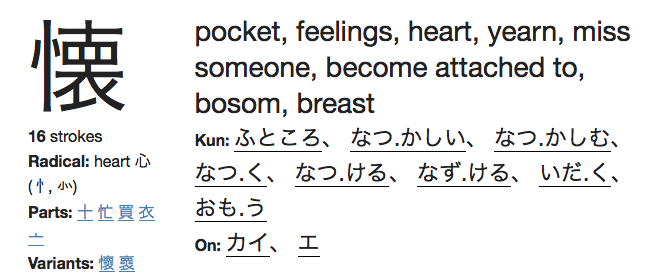

Japanese writers are masters of nostalgia. I don’t know why or how this originated but we can see that nostalgia is a core part of Japanese culture. One of the most common Japanese words, one that you will hear every day in Japan, is Natsukashii or 懐かしい and it means (loosely translated) nostalgic.

Hear a song on the radio that reminds you of your childhood? Natsukashiiiiiiiii!

Taste a brand of sake that reminds you of your long-lost father? Natsukashiiii….

Read a great book that stirs up something intangible inside you? Natsukashiiii…

The meaning is baked right into the written character (or kanji) for the word. It’s about yearning, feeling attached, and missing someone.

While Japanese writers are masters of this emotion, Murakami reigns supreme as one of the best. I can only imagine how stressful writing Norwegian Wood must have been, having to tug on his own heart strings every day for months on end, because every page is heavy with the feeling of love and loss.

Again, this comes down to choosing what you will say and what will be left unsaid. It’s about choosing moments of silence in order to communicate intense feelings that words could not possibly scale.

Every single page of Norwegian Wood demonstrates Murakami’s adeptness at summoning nostalgia. One moment that particularly wrangled my heart was about two thirds of the way into the book when the main protagonist, Toru, is playing pool with the girlfriend of his womanizer friend, Nagasawa. Toru hasn’t played pool for many years. The last time he played was after his best friend, Kizuki, killed himself. It’s a poignant description earlier in the book where we are left to conclude that Kizuki wanted to play one last perfect game before he died. Then, years later, we get this scene:

She got three in a row, then missed on the fourth try. I managed to squeeze out a point, then missed an easy shot.

“It’s the bandage,” said Hatsumi to comfort me.

“No, it’s because I haven’t played for so long,” I said. “Two years and five months.”

“How can you be so sure of the time?”

“My friend died the night after our last game together.” I said.

“So you stopped playing?”

“No, not really,” I said after giving it some thought. “I just never had the opportunity to play after that. That’s all.”

“How did your friend die?”

“Traffic accident.”

That’s it. They go on playing pool. There’s no lengthy internal monologue about why the main character lied. We know why he lied. And we feel the pain of his decision to lie so much more because it is given room to develop on its own. This space opens up around those two last words and allows nostalgia, or natsukashii, and intense and painful longing, to develop.

3. Juxtaposition – Create A Tapestry More Beautiful Than Life

I say tapestry because novels resemble tapestries more than an actual snapshot of life. Norwegian Wood lends itself well to having slices from different times fixed side-by-side because of the nature of the narrative itself: an older man looking back on his past. But even if you’re telling a story from the third person omniscient perspective and it isn’t trying to be particularly profound, you can still learn a lot by studying how Murakami selects what scenes to put next to each other.

One striking example of poignant juxtaposition in Norwegian Wood is the hand job in the meadow scene placed right after a tragic description of Kizuki’s suicide. Both scenes are incredibly touching and are infused with the essence of each other due to their placement.

This is a great literary tool to take advantage of when you want to effectively leave things unsaid yet still have them practically yelling at the reader. Each of these scenes would take on an entirely different feel and quality if they were swapped out and placed next to another scene. There’s also the fact that they are basically polar opposites and are very jarring and unusual being put close together. One is about death, the other about life. One about love and loss, the other about love and gain. One is massive, the other is minuscule. Minutiae side-by-side with a life-altering event.

4. Create Gaps And Occasionally Furnish Them With Jewels

Murakami’s writing style in Norwegian Wood is very sparse, minimalist, and heavily reliant on the reader filling in their own meaning, reading, and picture of the scenes and characters. Nothing is overwrought. Everything is understated. So much so that many readers could easily glide over the pages and miss the meaning.

These gaps are tremendous for creating the kind of narrative that slowly slips under your skin and into your soul, rather than one that batters at the door and is refused entry. It’s like a smack addiction. You don’t know you’re hooked until you are too deep to doing anything about it.

These gaps are also great because every now and then you can introduce a couple of concrete details that glimmer like jewels in the narrative. They stand out and are all the more poignant because these details have clearly being chosen specifically to stand out. They have broken free from the mire of subtlety and understatement and they pierce you to the core.

One such moment in which Murakami introduces rare concrete details is after Kizuki’s suicide, when Toru goes to university for the first time. We’ve just been told that Kizuki fed a gas pipe into his N-360 car and taped the window shut. After that, the scene is swept over, as though the thought is too difficult to bear. But some details escape free. Details that make chills run over your arms. Details like this:

There was only one thing for me to do when I started my new life in the dorm: stop taking everything so seriously; establish a proper distance between myself and everything else. Forget about green baize pool tables and red N-360s and white flowers on school desks; about smoke rising from tall crematorium chimneys, and chunky paperweights in police interrogation rooms.

We see the pool tables as vividly as Toru. We see the N-360 as vividly too. But we already knew these details and their significance. Then, completing the rule-of-three, Murakami offers another image, that of the white flowers on school desks. We are not told how the school handled the tragedy of Kizuki’s death. But we don’t need to be told. That image speaks volumes. Then we have more images with the smoke from the crematorium chimney and the paperweights in police interrogation rooms. Again, we are not told anything about these instances but we see a very clear progression with very little being said. We feel what the narrator wishes he could forget. And we feel it intimately.

5. Even (Especially) In Tragedies, Use Humour Often

Something that always fascinated me about studying Shakespeare’s plays was that the tragedies were funnier than the comedies and the comedies were more tragic than the tragedies (right up until the final act that is). We actually see this in all great literature. Tragedies that are filled with doom and gloom from start to finish end up feeling farcical. We reject the tragic experience. It means nothing to us. Likewise, comedies need to have a lot of shit going wrong. In fact, a lot of sitcoms would work well as tragedies if it weren’t for their inane laughter tracks.

Murakami uses humour extremely well. He uses it to make the tragic more tragic and the poignant more poignant. In an interview with The Paris Review, he actually says that he tries to inject a joke or some humour every 10 pages. I think that’s a great formula to follow if you are also writing drama. To paraphrase David Foster Wallace: the greatest truths and tragedies are best expressed in the form of a joke.

Humour is also a very effective fastening rod for combining many of a work’s themes together. Take this one scene of dialogue for example between Toru and Midori that effectively combines comedy, tragedy, love, sex, poignant juxtaposition, nostalgia, and gaps for meaning to arise:

“Tell me, Watanabe,” Midori said, looking up at the dorm buildings, “do all the guys in here wank – rub-a-dub-dub?”

“Probably,” I said.

“Do guys think about girls when they do that?”

“I suppose so. I kind of doubt that anyone thinks about the stock market or verb conjugations or the Suez Canal when they wank. Nope, I’m pretty sure just about everybody thinks about girls.”

“The Suez Canal?”

“For example.”

“So I suppose they think about particular girls, right?”

“Shouldn’t you be asking your boyfriend about that?” I said. “Why should I have to explain stuff like this to you on a Sunday morning?”

“I was just curious,” she said. “Besides, he’d get angry if I asked him about stuff like that. He’d say girls aren’t supposed to ask all those questions.”

“A perfectly normal point of view, I’d say.”

“But I want to know. This is pure curiosity. Do guys think about particular girls when they wank?”

I gave up trying to avoid the question.

“Well, I do at least. I don’t know about anybody else.”

“Have you ever thought about me while you were doing it? Tell me the truth. I won’t be angry.”

“No, I haven’t, to tell the truth,” I answered honestly. “Why not? Aren’t I attractive enough?”

“Oh, you’re attractive, all right. You’re cute, and sexy outfits look great on you.”

“So why don’t you think about me?”

“Well, first of all, I think of you as a friend, so I don’t want to involve you in my sexual fantasies, and second – “

“You’ve got somebody else you’re supposed to be thinking about.”

“That’s about the size of it,” I said.

“You have good manners even when it comes to something like this,” Midori said. “That’s what I like about you. Still, couldn’t you allow me just one brief appearance? I want to be in one of your sexual fantasies or daydreams or whatever you call them. I’m asking you because we’re friends. Who else can I ask for something like that? I can’t just walk up to anyone and say, “When you wank tonight, will you please think of me for a second?’ It’s because I think of you as a friend that I’m asking. And I want you to tell me later what it was like. You know, what you did and stuff.”

I let out a sigh.

“You can’t put it in, though. Because we’re just friends. Right? As long as you don’t put it in, you can do anything you like, think anything you want.”

“I don’t know, I’ve never done it with so many restrictions before,” I said.

Murakami has many such scenes like this to break up some of the angst and heartache that riddles the book. It’s interesting to note that he compartmentalises his comedic and tragic aspects. For example, when he wants to make you laugh, he’ll bring out Midori or he’ll let Toru tell an anecdote about his geeky roommate, dubbed Storm Trooper. This is a great technique to learn how to write humour effectively: anchor comedic moments to specific characters and symbols.

6. Learn How To Tell A Story-Within-A-Story

Study how Murakami uses the story-within-a-story convention in Norwegian Wood. Conrad is a master of this convention and so is Murakami but Murakami has certainly learned a thing or two from Conrad because the characters discuss him with great respect. I like to think of this as an homage to the great writer and a little nod to the story-within-a-story device being employed.

Study how Murakami is able to have multiple characters regale and hook you with their own stories. Study how the character of Reiko is even able to split her own story up into two parts and create a mini internal cliffhanger within the story itself. This is done to such great effect that it is easy to forget you are reading a story and not actually living in the world Murakami has created.

On top of all this, the entire book is, of course, one giant story-within-a-story in much the same way that Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is a story within a story.

7. Use Music As A Refrain

Study how Murakami consciously uses music as a refrain throughout Norwegian Wood. He continuously comes back to The Beatles, among many other musicians evocative of the time period, and he does this consciously in order to create a unity, a harmony, among the disparate memories told by the backwards-looking narrator, whilst also increasing the sense of nostalgia and longing.

Music, particularly The Beatles, stands as an important motif throughout the book with characters continuously paying to hear one another play ‘Norwegian Wood’, as though they’re also trying to return to a past or lose themselves in a symbol of hope.

8. Keep The Reader Guessing

Throughout the entire book, the reader is left guessing as to which character Toru will eventually end up with: Naoko or Midori?

Murakami crafts this guessing game so expertly because, once again in the vein of ensuring that nothing is overwrought, it doesn’t even seem like a guessing game. It doesn’t even seem relevant to the story. This feels more like a side thought that we, the reader, are simply preoccupying ourselves with as we fly over the memories of Toru’s past.

It looks equally impossible that Toru will end up with either of these women. And for wildly different reasons. And yet he does.

Each reader will have a character that they are rooting for. The whole way through the book, I was rooting for Midori to be the one that Toru ends up with. It struck me about halfway through the book that a story without a character or cause to root for is not much of a story at all. So give your readers someone or something to cheer for. Study how Murakami does this if you want to seem extra clever.

9. Use Symbolism To Structure Characters

The characters in Norwegian Wood all seem to stand for a separate ideal, whilst the main character wades through them and tries to make sense of it all. Many writers believe that characters have to be as real as the people who fill our everyday lives. They draw up long biographies for each one and the result is that characterisation can feel forced. But Murakami’s characters are archetypes. They are not real people but instead speak to very special, very intimate, core parts of ourselves. They speak to qualities that all of us can identify with. As such, they may be archetypes but they feel more real, more affecting, than any character that was conceived with a 100-page biography rather than a symbol for their essence.

Murakami touches on this subject in his Paris Review interview:

My protagonist is almost always caught between the spiritual world and the real world. In the spiritual world, the women—or men—are quiet, intelligent, modest. Wise. In the realistic world, as you say, the women are very active, comic, positive. They have a sense of humor. The protagonist’s mind is split between these totally different worlds and he cannot choose which to take. I think that’s one of the main motifs in my work. It’s very apparent in Hard-Boiled Wonderland, in which his mind is actually, physically split. In Norwegian Wood, as well, there are two girls and he cannot decide between them, from the beginning to the end.

If you want to learn more about creating characters (rather than people), I highly recommend Aaron Sorkin’s Screenwriting Masterclass.

10. Keep Experimenting

It is important to realise that Norwegian Wood was Murakami’s experimental novel. Even though it is the one that seems the most “normal” out of his oeuvre, this was the challenge Murakami issued himself. He wanted to write a straight novel and a bestseller just to prove to everyone else that he could. Then he could go straight back to his more Murakami-esque world.

What was the result of this experiment?

It propelled Murakami to international fame and fortune. It put him on the literary map. And it also resulted in one of the best novels of the 20th century.

You can buy Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami here.

All quotes taken from the 2003 Vintage version of Norwegian Wood by Haruki Murakami and translated by Jay Rubin.