“How do I not be nervous?”

I hear that a lot.

It’s a common question from the people who come to me for advice about getting into top universities.

What they’re really asking is how they can not feel fear.

But it’s not socially acceptable to admit you’re scared. Saying you’re nervous is a lot more relatable.

Regardless, my reply is always the same.

“What’s wrong with being nervous?”

I still feel fear in every situation where I’m invested in the outcome.

I’m terrified of looking stupid.

Petrified of losing – face, money, time, respect. I’m scared. And I feel that fear coursing through every inch of my body. But I’ve long since rewired my brain to interpret fear positively.

Fear keeps me alive. Fear shows that I am alive. Fear is my friend and I work with it, never against it.

“Fear is our ally. Fear confirms us. Fear is energy that is convertible to power – our power.”

Befriend your fear.

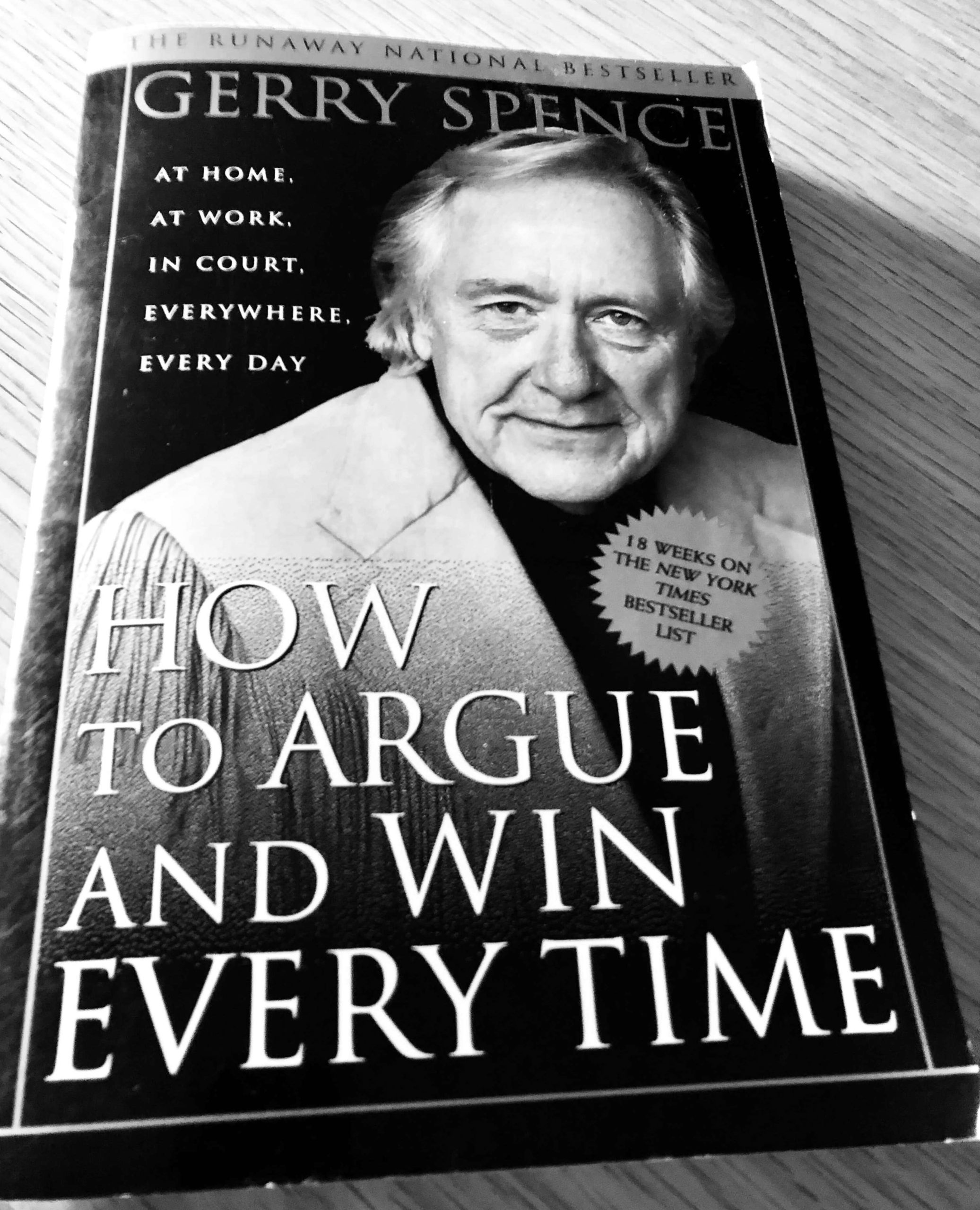

This is the message at the heart of one of the best books on persuasion and influence you can ever read:

How to Argue and Win Every Time by Gerry Spence

If you want to learn how to argue and win, how to be more persuasive, how to convince, compel, and persuade people effectively, wouldn’t you want to learn it from one of the most successful trial lawyers?

A man who has never lost a criminal case.

This man, Gerry Spence:

One of the many things I love about How to Argue and Win Every Time is the fact that the entire book helps you to reframe old unhelpful thinking patterns.

Spence’s book is in fine company and sits on my shelf with other books that have resulted in serious paradigm shifts and complete rehabs of how I see the world:

- Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations

- Stephen Covey’s 7 Habits of Highly Effective People

- Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (review here)

In the mother of all reframes, one that will serve you well as a mindset for your entire life, Spence connects fear, arguing, energy, and affirmation of being together into one super ball of magnetic power.

Fear confirms that, at my heart-core, life, not death, is the authority. The dead are not afraid. Fear is the painful affirmation of my being.

We’ve been taught wrong.

We’ve been over-therapised and over-prescribed zombifying pills, and society has instilled in us the belief that anxiety, fear, trepidation are all unnatural things that we should go through life without.

We should just be happy, without reason, 24/7.

Wrong.

Real men cry.

Real men are painfully connected to the core of their being.

And when you can learn to connect to that wellspring of human life, you will have no problem helping, leading, teaching, loving, enjoying, and claiming justice.

Who is the more brave – the small boy standing on the edge of the stage singing his first solo before his Sunday school class, or the great opera diva singing at the Metropolitan Opera?

Remember this when you see others taking their first steps.

Remember this when you take your own first steps.

Remember this when you take your own first steps.

It’s okay – in fact it’s marvellous – to do things badly.

I’m reminded of Jesus’ parable of the widow who, unlike the rich men offering bags of money, could only offer two coins, but they were everything she had.

Fear is energy. If you feel your fear, you can also feel its power, and you can change its power to your power.

What a reframe!

This is a powerful exercise in positive self-talk, plus it teaches you to check into the present moment.

Every time I have felt my hands literally quake with fear, focusing on the feeling has been the only thing to diminish it.

When I feel my breath become staggered and shallow, and my heart beat won’t slow down, I breathe deeply and consciously.

When you look fear in the face, it shrinks in size.

How do you get a monkey off your back?

You grab it and turn it around to face you.

Where does fear come from?

When you’re back stage before a presentation, can hear the crowds of people waiting, can see the spotlight hit the podium, why is it you tremble and clam up?

Often it’s because you’re not convinced that you have the right, the authority, to be doing what you’re doing.

If you were convinced that you were the world’s lead expert on whatever topic you were about to talk about, convinced beyond a shadow of a doubt, I can assure you that you would stride onto the stage without a wobble or a falter and you’d give the best damn speech of your life.

The key to overcoming this is this:

Argue from your own authority.

Spence calls this finding your “soul-print”.

Why should people listen to you?

Because you have your own authority and that is enough.

How to Argue and Win Every Time is full of great passages. Huge beautifully written, poetically wrought, chunks of love and wisdom that defy culling. Here is one such passage that I cannot bear to clip, so I quote it here in full, bolding the lines that jumped out at me:

Wisdom usually does not fall from high places. The mighty and the splendid have taught me little. I have learned more from my dogs than from all the great books I have read. I have learned more from my children than from all the professors who have importuned themselves upon me in the exercise of their tenure. The wisdom of children is the product of their unsullied ability to tap their innate fund of knowledge and innocently to disclose it. The wisdom of my dog is the product of his inability to cancel his wants. When he years to be loved, there is no pouting in the corner. There are no games entitle “Guess what is the matter with me.” He puts his head on my lap, wags his tail and looks up at me with kind eyes, waiting to be petted. No professor or sage every told me I might live a more successful life if I simply asked for love when I needed it.

The number one thing I learnt from Rilke was the idea of never asking others for advice. Become your own source of advice, because you will always be the best source.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t surround yourself with knowledgeable people who can steer you in the right direction. But if you take Doris Kearns Goodwin’s MasterClass in leadership lessons from great US presidents, you’ll learn that though Lincoln and Roosevelt built respectable cabinets, the process of filling them with people who could dispense good advice was incredibly difficult – you must, first and foremost, be capable of being your own guide.

As Spence says:

No act is more suicidal than casting aside one’s personhood and replacing it with the alien authority of another.

Do you know how revolutionary it is to go from self-doubt to fully immersed in the belief of your own personal power?

The way you walk, talk, and look changes.

People smell it.

What is winning?

Spence shares the same definition of winning as top FBI hostage negotiator Chris Voss in his Negotiation MasterClass.

Winning is getting what we want, which often includes assisting others in getting what they want. Winning may forward a just cause. It may help strangers, it may discover the truth. Winning may help a loved on to succeed, a child to bloom, an enemy to see us in a new light. But, whether winning is winning for ourselves or for others, winning is still getting what we want.

And we get what we want by helping others to get what they want.

Arguing is not the same as disagreeing.

We’re dancing, not wrestling.

People who disagree “never win, for they never achieve what they want.”

This translates beyond the courtroom or boardroom. In your personal relationships, “trust begets trust” and demonstrations of love are “the most powerful of all arguments”.

Like in judo, you move with your counterpart, not against them.

All power, yours and theirs, is yours.

Power is perception.

Another excellent reframe is Spence’s definition and understanding of power.

So many people – particularly men in top positions – fancy themselves as powerful, but are actually mistaking power for disagreeableness. It’s all about getting on top of your opponent. It’s never about collaboration or win-win. They have to feel the other person has lost in addition to them winning in order to feel power. But this is not power.

Understanding how power works: Power is first an idea, first a perception. The power I face is always the power I perceive. Let me say it differently. Their power is my perception of their power. Their power is my thought. The source of their power is, therefore, in my mind.

If you wish to see a demonstration of this principle, watching the documentary Pumping Iron. Watch how Arnold Schwarzenegger gets inside Lou Ferrigno’s head.

The power others possess is the power I give them. Their power is my gift.

I give people power every day of my life.

I respect their authority on certain subjects and respect their virtues and integrity as human beings.

But I can take that power away in a heartbeat.

You are not entitled to the power you hold over me.

The power you hold is a gift that I bestow.

And that gift is always conditional.

The power to judge: All power entities attempt to judge us. We are told that God judges us. Our parents judge us and the judge judges us. But they have the power to judge us only so long as we have given them such power. Otherwise they judge us only for themselves, which was their right in the first place.

Power corrupts, but power is always lonely.

Speaking of the judge Spence says: “No person needs a friend more.”

Think of how lonely it is to be the boss, hated by the old friends who you now command.

When you understand this, befriending and help those in power becomes second nature.

Anyone can be credible, but we must risk telling the truth – about ourselves.

Every positive outcome in my life has been the result of connecting with a scarily deep level of self-awareness and truth.

Here’s another great passage from Spence:

The first trick of the winning argument is the trick of abandoning trickery. Most of us can talk about ourselves – a little – and zoom in on our feelings – a little. But most of us do not tell much of the truth about ourselves. We hold back our hurt, our anger, our deep dread. We fear to reveal our fear, our joy, our jealousy, our hunger, our ideas, our insecurities, ourselves. Credibility comes out of the bone – deeper yet, our of the marrow. We puff and swell, hoping to appear like a frightening Goliath. But do we not remember David? Great pretences win nothing.

This is how you stand out in everything – relationships, friendships, careers, passions, vocations.

To win, we must be believed. To be believed, we must be believable. To be believable, we must tell the truth, the truth about ourselves – the whole truth.

This is why I believe truthfulness to be Aristotle’s most important virtue. It’s the beating heart in the center of a well-functioning ethical human being.

“We must argue from the place where the frightened child abides.”

We spend our whole lives trying to get as far away from the feeling of fragility that childhood bestows.

We want to seem adult, feel adult, be adult.

But no matter how old you are, how experienced you are, you will always have that child still inside you.

In the same way that you must embrace your fear, you must find a way to return to that child.

“Credibility is becoming the child.”

Credibility and winning isn’t about technique or saying the right words. It’s a mindset and state of being.

We communicate not only with words, but with the various sounds of words and their rhythms. We speak with silences. We speak with hands, and bodies, with physical words – the way we pose or stand or more.

As Chris Voss points out, in conversations people like the content 7%, the tonality 38%, and the body language 55%.

If we’re looking at relative percentages, that means tonality is 5x more important than words spoken. And how you stand, look, and move is 7x more important than the words spoken.

Our willingness to openly reveal our feelings in our argument nearly always builds our credibility.

The most effective trick I’ve ever learnt in personal relationships, in writing, in connecting with other people, is to abandon the tricks altogether and be vulnerable.

It is the most disarming thing you can do.

Reveal a genuine vulnerability to someone and watch what happens in their eyes.

You can see trust and affection developing in real time.

With men, the most common negative emotion is anger. A lot of men are quick to anger, but I don’t believe a lot of men are angry. I believe this anger, in the majority of time, is masking fear.

So when you’re angry, ask yourself:

- What are you afraid of?

- What fear is causing this?

But should we go so far as to confess our fear to the Other? I say that acknowledging the truth, even the truth about our fear, perhaps especially the truth about our fear, creates credibility.

Being truthful about your fears is only one half of the puzzle when it comes to winning the argument.

The other half is being truthful about what you want.

Most people will never be truthful about the fear they feel. Similarly, most people will never be truthful about what they want.

Hearing what someone wants is refreshing.

No dancing around the subject. No sly games. Upfront honesty about exactly what you want, lay it all on the table.

Weeks after the jury had returned its verdict, I talked to one of the jurors who had fought very hard for the acquitted of Mr. Weaver. “You told us what you wanted,” she said. “That’s what I wanted too. I was glad you were up-front about your wants. It made it easier for us to understand you. We wanted to give you what you wanted.” The power of the argument was in telling the jury about my dream, the truth for me – what I wanted for me.

Be honest about what you want.

People are afraid to tell others what their services are worth. They are afraid to ask the doctor what the doctor expects to be paid. In a civil money case, I tell the jury outright that I want them to give my client money, and how much. When the jury retires to reach its verdict, it knows exactly what I want. Such openness also serves my credibility. How can we feel comfortable with someone who we know wants something from us but who will never be honest about it?

Spence says, “I get it because I ask for it.”

Remember that Bible passage?

Ask and it will be given to you. Seek, and you will find.

In getting what you ask for, however, you must keep in mind two things:

- Admitting your own prejudices strengthens your credibility.

- “No matter how skilfully we may argue, we cannot win when the Other is asked to decide against his self-interest.”

So how do we win?

Get your counterpart to acknowledge their prejudice, then fully empower them.

Spence will often address juries or those he is arguing with in this fashion:

Try to pretend you are the ‘ultimate authority in the universe.’ You have absolute power over all living things on the earth. Pretend that your desire, as the one with absolute authority, is to render pure, perfect justice. Do you think you could imagine this – just for the moment?

What’s great about this is you can use this on yourself too. This works as powerful self-talk.

How to Argue and Win Every Time is also a blueprint for creating compelling stories.

“The strongest structure for any argument is story.”

And what’s the least important part of a story?

The words.

Ask James Patterson. Ask Dan Brown.

True story, story that has the power to move, isn’t elegant.

It comes from the heart zone and speaks to everyone because it is so natural to our species.

The story is the easiest form for almost any argument to take. You don’t have to remember the next thought, the next sentence. You don’t have to memorise anything. You already know the whole story. You see it in your mind’s eye, whereas you may or may not be able to remember the structure and sequence of the formal argument.

Spence goes deep into the art of how to structure a story, a part that will serve any budding trial lawyer well, but I’ll put the main points you need to remember here.

If you want to go deeper, you can (and should) get the book from Amazon.

The story is always built around a thesis, a point of view that is advanced by the argument. Ask yourself, “What do I want?”

What you want = your thesis.

Here are some further prepatory questions that will inform the structure of your story:

- What do we want?

- What is the principle argument that supports us?

- Why should we win what we want? That is, what facts, what reasons, what justice exists to support the thesis?

- And, at last, what is the story that best makes all of the above arguments?

Once you’ve written the argument and structure (in an exploratory stream-of-consciousness manner), circle in red the key words. Write a descriptive phrase or metaphor that symbolises the soul of the case – call it the theme.

The argument’s theme supports the argument’s thesis.

Then visualise your arguments.

Don’t intellectualise them.

Action verbs, action pictures – the man trudging home to an empty house, the blacksmith fashioning the horseshoe for old Ned – avoid the abstract that tells us so little. When people explain things to me in the abstract, I grow impatient. Give me an example, I most often say. Show me how you do it. Don’t tell me. Draw me a map. Draw me an illustration, a chart. Show me a time line of the events that have occurred. Let me see what happened and when. Don’t tell me the man was hurt and suffered a broken femur. Show me a picture of his broken leg. Show me the X-ray.

Another powerful persuasion tactic is that of concession, what Chris Voss calls “Accusation Audits”:

I always concede at the outset whatever is true even if it is detrimental to my argument. Be up-front with the facts that confront you. A concession coming from your mouth is not nearly as hurtful as an exposure coming from your opponent’s. We can be forgiven for a wrongdoing we have committed. We cannot be forgiven for a wrongdoing we have committed and tried to cover up.

I have long inherently believed this, and if you want to see a dramatised display of what this looks like in a winning argument, check out the end rap battle scene from Eminem’s 8 Mile.

So when you want to win, you give the other the power, you tell the truth, and you be who you are. But you must also consider all of the potential reasons someone else may not even hear your argument.

Here’s a checklist. Could the other say yes to any of these?

- “If I accept your argument, will I feel as if I have given in?”

- “I am afraid I will be seen by you as weak.”

- “Will I lose your respect if I accede?’

- “Will I suffer some sort of loss of self?”

- “What else might I lose? Will I lose money, stature, power, position?”

- “Will I have to admit I am wrong?”

- “Will I feel as if I have failed?”

- “Will I find myself in an uncomfortable, even untenable position?”

- “Will I be expected to do something I do not want to do?”

- “Will I suffer loss, any loss?”

- “Will my power be diminished?”

- “Will my giving in renew old, painful memories of a previous capitulation?”

- “Will I have to take the risk of thinking about something new?”

- “In short, does your argument in appearance or in fact threaten my well-being?”

Your mission is to ensure that these needs are all taken care of and preemptively disarmed.

Empower the Other to reject you.

Empowering people makes them trust you.

When a good doctor wants his patient to undergo a necessary operation, he empowers the patient to exercise his or her own judgement. “See another doctor. Read this literature. Consult other patients who have faced and recovered from the same ailment. The decision is yours,” the doctor says.

And don’t smile too much.

That’s another thing most sales books get wrong.

Smiling too much is disingenuous and people can feel it.

Smiling a lot, assuming the stance of the nice guy, does not lend credibility and does not open the Other to our arguments. A smile should not cover our feelings. Instead, we should smile when we feel like smiling.

This is all part of charisma.

Become in touch with your feeling.

It’s the feeling behind the words not the words themselves that carry the power.

An exercise Spence suggests to develop this goes like this:

Read the phone book: We read the phone book because he words make no difference. The power is not in the meaning of the words, but in their sounds. Read the phone book out of your angry feelings. Read it out of your joy. Read it to express sorrow. Read it to express supplication. Read it to demand justice! Read it to tell your Mother that you love her, your Mother Earth. She will know. She will understand.

To argue on behalf of someone else, you must crawl inside their carcass and feel what they’re feeling.

To argue on your own behalf, you must connect with the universe of feeling deep inside you:

Focus on your feeling. Don’t forget, you must feel your feelings, feel your passion for the argument you are making. Remember, nothing in, nothing out. Feel the fervour that comes steaming up when you seek justice – justice for a raise, justice for a promotion, justice for a wrong done to you or a loved one. Feel your passion surging for a reform. Feel the love that caresses, feel the joy! Feel the feelings.