Syllabus creation is artistic output. Akin to ice sculpture, Cecchetti ballet, and bebop jazz.

I used to pore over the syllabuses of Kurt Vonnegut, David Foster Wallace, and W.H. Auden. But even with these greats, even cerebrally salivating over their reading lists and essay assignments, I couldn’t help but feel as though something humanistic was missing.

We do all this reading, but for what?

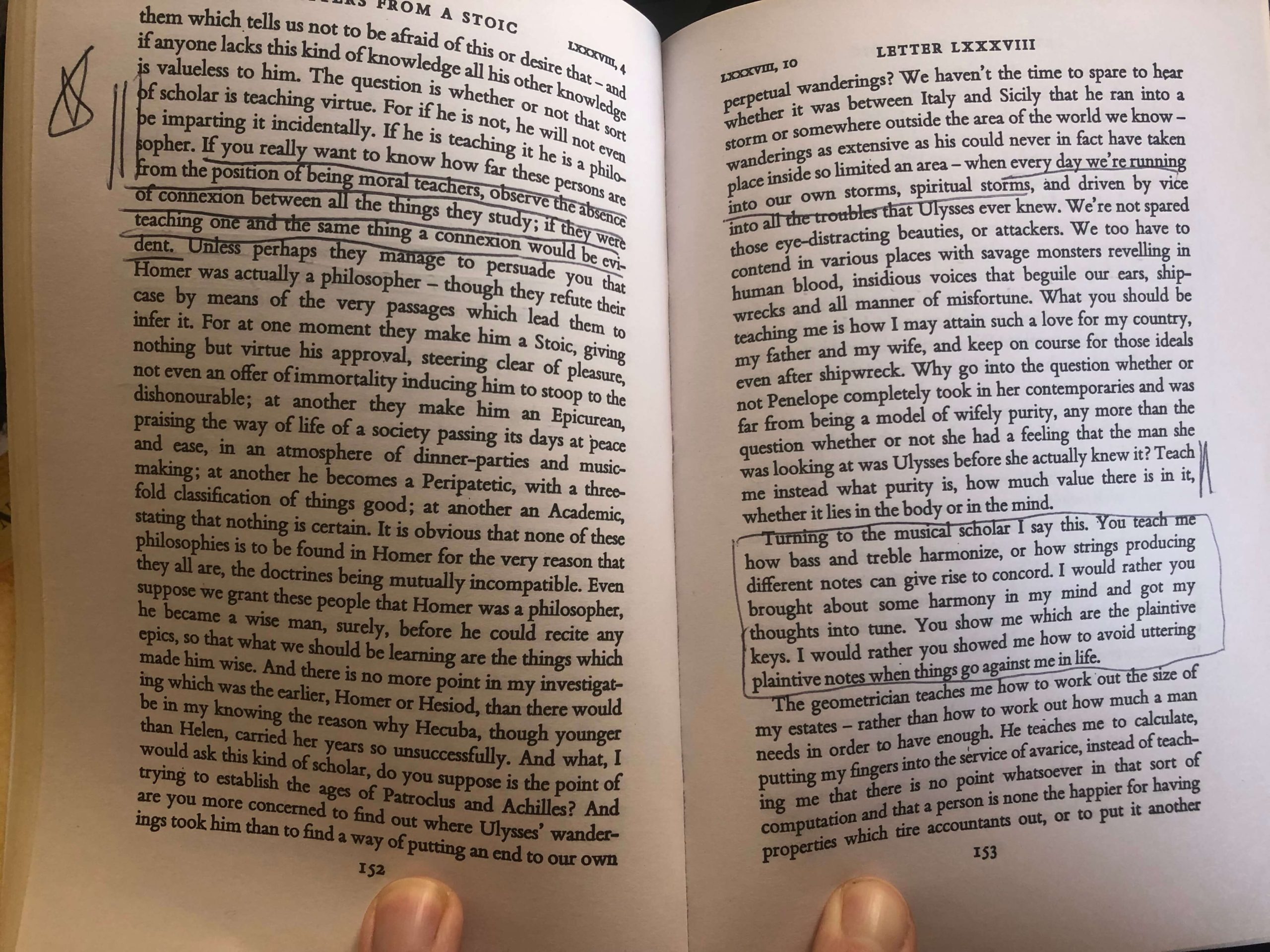

You know you’re in sync with the simulation when serendipity becomes the norm. I took my copy of Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic out on the balcony along with my cup of coffee this morning. Flipped to a random page and found, in letter LXXXVIII, Seneca stealing my ideas about education over 2,000 years before I was born – how dare he!

A summation of Seneca’s thoughts on the matter:

- Time should been spent focused on money-making pursuits ‘only so long as one’s mental abilities are not up to dealing with higher things. They are our apprenticeship, not our real work.’

- Real work = liberal studies because they make a person free (a liber) through the ‘pursuit of wisdom’.

- We talk of poetry, maths, science, but what of them if they do not lead to virtue?

Tolstoy and Seneca are in agreement. Here’s what Seneca says about teachers (my bolding):

The question is whether or not that sort of scholar is teaching virtue. For if he is not, he will not even be imparting it incidentally. If he is teaching it he is a philosopher. If you really want to know how far these persons are from the position of being moral teachers, observe the absence of connexion between all the things they study; if they were teaching one and the same thing a connexion would be evident.

And here’s Tolstoy in Anna Karenina (again, boldings are mine):

Levin had come across the articles they were discussing in magazines, and had read them, being interested in them as a development of the bases of natural science, familiar to him from his studies at the university, but he had never brought together these scientific conclusions about the animal origin of man, about reflexes, biology and sociology, with those questions about the meaning of life and death which lately had been coming more and more often to his mind.

Listening to his brother’s conversation with the professor, he noticed that they connected the scientific questions with the inner, spiritual ones, several times almost touched upon them, but that each time they came close to what seemed to him the most important thing, they hastily retreated and again dug deeper into the realm of fine distinctions, reservations, quotations, allusions, references to authorities, and the had difficulty understanding what they were talking about.

Isn’t that always the case?

If you went to university, that surely sounds familiar. I remember my Oxford tutorials. I remember theological debates on Oriel’s third quad, croquet mallet in hand.

Every single time you seemed on the cusp of connecting these facts to higher ideas, these academics always seemed to shun away, bury their head in quotations, allusions, and references to authorities.

Teach these boys and girls nothing but Facts. Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else. You can only form the mind of reasoning animals upon Facts: nothing else will ever be of any service to them. – Hard Times, Charles Dickens

Facts are rarely interesting in and of themselves.

Counting syllables and seeking out internal rhymes has never been the primary pleasure I gained from Shakespeare.

Talk to me about science – but let what you teach create a mountain with which to reach the eternal!

This, I believe, is Seneca’s complaint. I could be wrong. But I think Seneca is calling for educational revolution. He talks about the teacher of philosophy, the teacher of geometry. Read what he says of the musical teacher:

You teach me how bass and treble harmonise, or how strings producing different notes can give rise to concord. I would rather you brought about some harmony in my mind and got my thoughts in into tune. You show me which are the plaintive keys. I would rather you showed me how to avoid uttering plaintive notes when things go against me in life.

Give me a teacher who makes me into a better human as they teach me to sharpen a skill.

A teacher who says “2 + 2 = 4” and “we’re all capable of evil” in the same breath.

A teacher who teaches you of the fall of kingdoms across the chequered chess board, copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War beneath the captured pieces.

A teacher who sings an aria, shows you how to hit the middle C, then explains how to love by virtue of studying Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

A teacher who writes haiku, makes udon, and compares collectivism with its counterpart, all in the guise of learning Japanese.

Give me a boxing coach who teaches me to control my temper along with my jab.

This is the mindset the teacher must adopt in order to create a compelling syllabus.

How else to create a compelling syllabus?

Create the course that would make YOU say hell yes and sign up in a heartbeat – the course that would make YOU want to do the reading immediately and turn up in the front row of every lecture.

Creators are foremost fans. Country, gospel, and folk records littered the apartments and constantly span across the turntables of Jagger, Richards, Taylor, Wyman, and Watts. Then Exile on Main St. was born. So deepen your fanitude to your art. Become a fan of your own classes.

Picture the ideal – who stands behind the lectern? What do they discuss? And why?

Put the pressure on by taking it off.

Become a child again, engage with your sense of prehistoric play.

Syllabus creation, lecture composition, sermon planning is finger-painting. Brushes sweep across the canvas dragging a multi-coloured family of bristles.

How do you market? How do you make money?

You look at the marketing that worked on you. Think of the places you throw your money. Assuming you’re your ideal audience. Because that’s another thing. People will ask, ‘Who are your lectures aimed at?’ To which you’ll reply ‘Everybody’ and thus reveal your naivety.

Your classes aren’t for everybody.

You go wide by niching down. The same with writing. When you write a book, you pretend you have one person, someone close to you, sitting across the table from you and you want to keep their attention. The same helps when you crafting a syllabus.

Think of the people in your life that act as a mirror to you. The people you can’t help sermonising to. The people who listen with glee. If you don’t have at least a handful of people in your life that love to hang on your every word whilst challenging you (because that’s the caveat the differentiates sidekicks from sycophants), you likely have no business lecturing anyone at all.

You change the world by changing yourself and expanding your circle of influence. Begin with the one looking at you in the mirror. Go on walks and let long monologues unravel in your mind. Tape yourself speaking. The sooner you can get over the sound of your own voice, the sooner you can start the important business of self-examination. Then move to those closest to you: lover, brother, friend. Then you think nationally. Then globally.

What’s the subject of your lectures?

It’s easiest to lecture on the subjects you know really well, whilst also have the enthusiasm to find out even more about. Treat your lectures and classes as arena’s to discover more about your subject. You should never fall into the fallacious thinking that you’re the expert (though you should be one) and you’re teaching the unwashed crowd. You are teaching. But they’re teaching you too.

Those to whom you lecture must be as smart as you are. They might not know the material you have to teach yet, but that’s a gap in knowledge, not the inability or difficulty to obtain knowledge.

The moment you think you’re smarter than, better than, your audience, you’re done for. Spiritual death will come soon. Think you’re lecturing to helpless morons and you’ll develop bags under your eyes from nights of restless sleep. This is true even for creatures that are below your intellect objectively speaking. How do you speak to a 7-year-old? How do you speak in a way that results in them developing quicker than their peers? I’ll tell you how you don’t speak: you don’t patronise.

Here’s the best case scenario for a typical 45-minute lecture: You know your subject well. You’ve conceptualised the ideas astutely. And yet, in the process of lecturing, you refine them so well, following relevant tributaries of thought, that you understand the subject on a deeper level by the end of the lecture.

And if you give that same lecture again?

You’re thinking deepens even more. The lecture becomes iterative. You change.