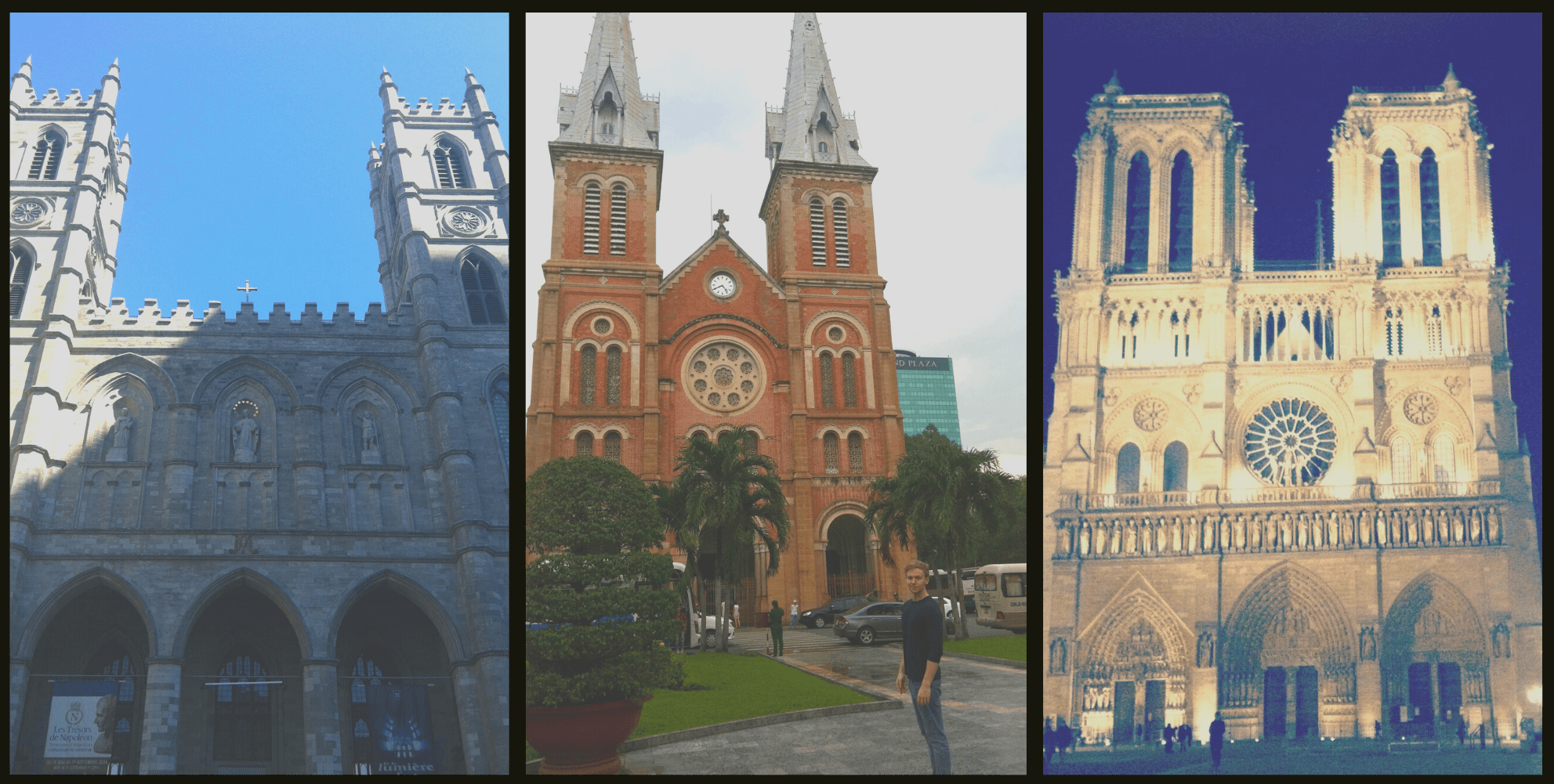

I’ve finally embarked upon reading the Sistine Chapel of literature. Or rather, I should say, the Notre Dame. I am reading Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (1862), and herein lie my thoughts.

The author of this review standing in front of the Notre Dame. Left to right: Montreal, Ho Chi Minh, Paris. Oh, to have been able to frequent them with Victor Hugo himself!

I am already in awe, so I have decided to do what I should have done with Anna Karenina. Tolstoy’s masterpiece was my lockdown companion. It took me six months to finish, and I truly lived with the characters: Levin, Vronsky, Anna, et al. I know them better than I know many of my friends. It was this novel which confirmed what I had long suspected of books: reading is not escapism, nor is it a surrogate experience, a fantasy.

Reading is experience, is life itself.

And I’ve cheated myself out of reading my impressions throughout my time spent in nineteenth-century Moscow with everyone. I shall not make that mistake again. Not when I have inhaled the first hundred pages of Les Misérables in the space of a few days, the bulk of which I stayed up well past my bedtime to enjoy.

I have never felt anything quite like this.

It’s like the first time you truly fall in love.

Some might express regret for not having arrived at this book earlier, but not me. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve come to truly understand how to read the great books. I read Nietzsche and Aristotle in my teenage years, but I didn’t have the experience to help me truly understand them. Les Mis would have been lost on me.

I moved to Vienna at the beginning of last year. Renounced my home in Japan, slowly and painfully came to terms with death, and experienced a year-long crisis of the soul that culminated in me walking the palace grounds of Schönbrunn, coffee in hand, completely alone, and perhaps, finally, on the cusp of some peace and understanding.

We’re now moving into a new decade, and the entire world has not handled it well. We come to the end of a tumultuous year, and I go into the next, not with a sense of foreboding and ever-increasing tyranny, the cowardice of letting resistance die until it’s too late on the constant periphery of my consciousness, but with a sense of comfort, vision, direction, purpose – walking through the cobble-lined streets of humanity’s shared soul with Victor Hugo holding my hand.

I’ve now read the first book, ‘An Upright Man’, of part one, ‘Fantine’, and I move into book two, ‘The Outcast’. I’ve met and become enamoured with Monseigneur Charles-François-Bienvenue Myriel, Bishop of Digne, and I’m becoming acquainted with Jean Valjean.

I rarely read reviews or commentary before completing a book, but I noticed some months back when I searched for what people had to say about this novel that some complained of Hugo spending too long at the beginning giving attention to a peripheral character before introducing the lead. How sad and unfortunate to be a reader who finds they must either endure or skip over time spent with Bishop Bienvenue.

I could have read a thousand pages of Bishop Bienvenue’s story.

Indeed, Tolstoy did something similar with delaying the introduction of Anna, even delaying the reader’s realisation that the real central protagonist was Levin (don’t get me started talking about the one time Levin and Anna actually meet – if you’ve ever seen the Michael Mann movie Heat, you’ll remember the electricity of the final meeting of Al Pacino’s character and Robert De Niro’s character – this was that in literary form). I know why Hugo is making us spend so time with this bishop. From a purely literary artifice perspective, we need to know and feel Bienvenue to be so eminently good because it will make that which comes next all the more poignant.

And we sure do feel it. I don’t believe I have ever felt butterflies in my stomach whilst reading a book (and this coming from an avid reader with an Oxford English Literature education). That’s why I compare this reading experience to falling in love. I feel on the verge of tears because… Why? Because the prose is so beautifully rendered? Because the author feels and communicates compassion and empathy for the whole of humanity so masterfully? Because spending time with Bienvenue makes me want to be a better person? Because when I’m not reading the book, I’m thinking of the book, and wondering how and whether I should make more efforts towards the saintly? All this and more. I can’t explain it.

All I know is this is the quickest I’ve ever read a book in which I’ve actively slowed down to drink in the writing.

Every sentence is like syrup.

Abstract distillations of the human condition quaffed, then savoured, then quaffed, then savoured – until you find yourself heady and drunk and in ecstasy.

I’m reading the Norman Denny translation of Les Misérables, available in 1231-page door-stopper Penguin paperback. I typically cover such paperbacks in marginalia. But I held back. When every paragraph forces you to pause, drags the breath out of your body, you feel a religious reverence towards the work.

This is my scripture.

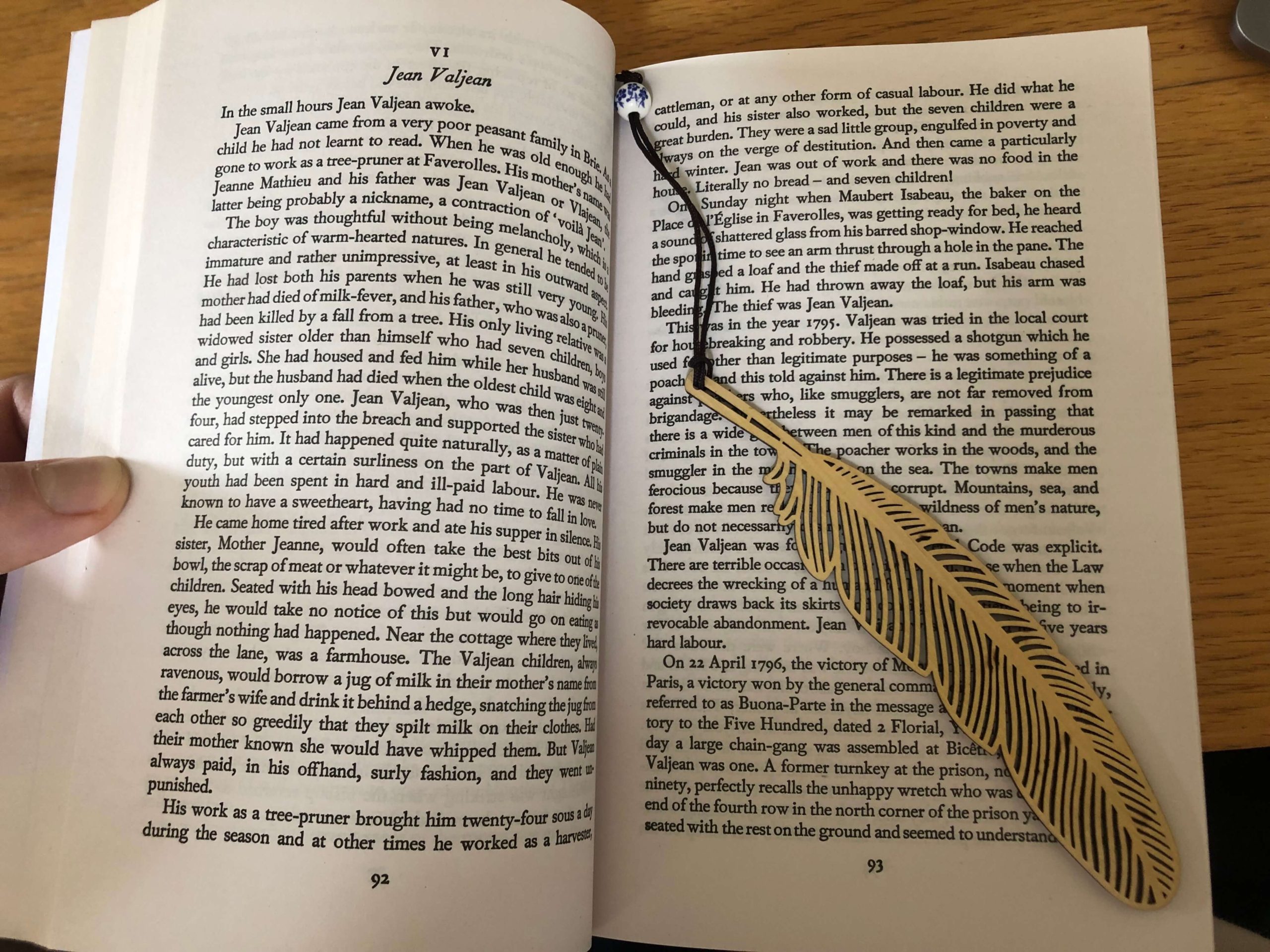

I’ve purchased a luxurious gold-painted mahogany bookmark with tassle and bead, which sits lovingly between pages 92 and 93 as I write this. But I finally marked the pages. I’ve penned an index on the frontispiece, alongside the date that I started the book. I like to put the date I finish a work, along with brief snapshot impressions, after THE END – a critical trick I picked up from fellow Pisces Montaigne, and so thought this to be a nice addition. (Interestingly, Victor Hugo is also a Pisces, like every great person I know – my girlfriend, several friends, Jack Kerouac, and my dear friend and mentor Misha, for whom I’m in deep debt and gratitude for having recommended this book, his favourite to me. Reading this work is a constant conversation with him.)

The index has two sections. One section is marked “monologues/dialogues”, and it’s hear that I will mark the sections of extraordinary exchanges between compelling characters. The Bishop’s conversation with the dying revolutionist is there. So is the Bishop’s meeting with Jean Valjean.

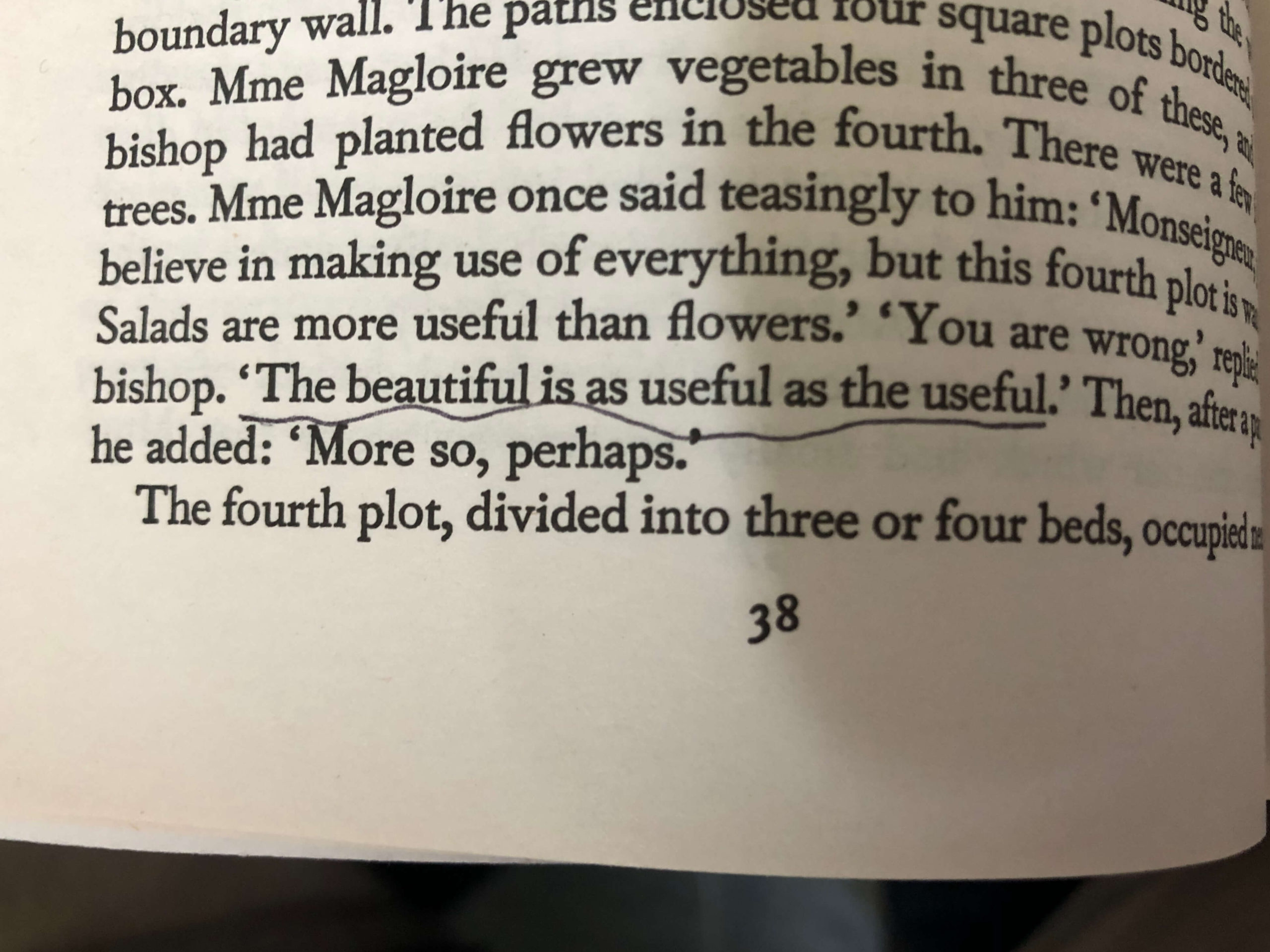

The other section is marked “digressions”, because Victor Hugo himself is a character (and great art lies in the digressions). He knows when to stand back and let the characters take over, but he interjects deliciously now and then, wrapping himself up in the history of the story (and why not? He lived this for decades, even drastically changing his opinions and needing rewrite the spiritual thesis that runs through the tapestry of this work). In this section, I could not help but store Hugo’s thoughts on the guillotine. There’s also a delightful rumination on the nature of success in chapter seven of part one:

“The populace is an aged Narcissus which worships itself and applauds the commonplace.”

This sentence is taken from an altar-sized sermon at the end of the chapter, one in which every word makes one ache.

I’ll now document some snippets that I wish to relish in the rewriting of them, each one hopefully making it into my personal creed:

- ‘You have come from an unhappy place. But listen. There is more rejoicing in Heaven over the tears of one sinner who repents than over the white robes of a hundred who are virtuous. If you leave your place of suffering with hatred in your heart, and anger against men, you will be deserving of our pity; but if you leave with goodwill, in gentleness and peace, you will have risen above any of us.’

- ‘The prophet may be bold, but a bishop must be cautious. He probably refrained on principle from looking too closely at those problems which are in some sort the reserve of the towering and iconoclastic intellects. A sacred terror haunts the threshold of Enigma; the dark portals are flung wide, but there is a voice which warns the passer-by not to enter. Woe to him who ventures too far! Men of genius from the boundless depths of abstraction and pure speculation, situated as it were above dogma, propose their theories to God. Their prayers audaciously invite discussion. Their worship poses questions. That is personal religion, loaded with anxiety and responsibility for those who dare embark upon it.’

- ‘His heart was given to all suffering and expiation. The world to him was like an immense malady. He sensed fever everywhere, sought out affliction and without seeking to answer the riddle did what he could to heal the wound. The awesome spectacle of things as they were enhanced his tenderness he was concerned only to find for himself and inspire in others the best means of comfort and relief. The theme of all existing things was for that good and rare priest distress in needs of consolation.’

- ‘From Lordship to Eminence is but a step, and between Eminence and Holiness there is only the wisp of smoke from a burnt voting-slip.’

- ‘Success: that is the message seeping, drop by drop, down from the overriding corruption.’

- ‘He would have made no bones about associating the son of Barabbas with the son of Herod. Innocence wears its own crown.’

- ‘The brutalities of progress are called revolutions. When they are over we realise this: that the human race has been roughly handled, but that it has advanced.’

- ‘Red is an all-embracing colour. How fortunate that those who despise it in a bonnet revere it in a hat.’

- ‘The guillotine is the ultimate expression of Law, and its name is vengeance; it is not neutral, nor does it allow us to remain neutral. He who sees it shudders in the most confounding dismay. All social questions achieve their finality around the blade.’

I am breathless at the prospect of continuing this work, already feeling it’s one of the few rare gems that will constitute part of my life’s work.