Books of poetry are like albums.

You know that feeling when you dust off Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks and spend the afternoon reclining? Or that feeling when you run through the park on a crisp morning with Morrison Hotel in your ears? Or when you spend years waiting for an artist to drop a record and it finally comes out and you spend the rest of the week humming the tunes?

It’s like that with poetry for me. I dust off slim Faber and Faber volumes, the ones issued under T. S. Eliot as editor, from Ezra Pound, W. H. Auden, and James Joyce. Plath is my Dylan, cummings my Morrison, and Armitage the poet whose work I hotly anticipate and murmur to the rhythm of my running feet.

Poetry is the least appreciated of all the literary art forms. Though I’ll accept anyone who wishes to argue stage plays take that position. The only time we read poetry is either in anthology form for school or the stuff scrawled on the public lav’s steel wall above the glory hole. Not good enough.

I get drunk on poetry every night.

Sometimes I pop open the good stuff in the morning and it sees me through the day. Occasionally I delude myself into thinking I can brew my own. But I’m tired of drinking alone.

I’ve stopped reading novels alone. Any significant work I’m reading becomes a book club. I do this with the people closest to me, but I also scale it in the forms of articles, podcasts, and videos. Now it’s time to scale the one thing I fear will never reach mainstream appeal – poetry.

Each week I’ll recommend you a slim volume of poetry that I’ve been getting drunk on.

Here are the rules:

- No anthologies. Some teacherly fuddy-duddy picked the same old poetic tripe, the same sonnets and villanelles that have been trotted out so many times they’ve become cliche, and packed them into a couple of anthologies and collections with tiresome chapter headings like “growing old” or “childhood”. That won’t do. We want the poetry world’s versions of Led Zep’s IV, Black Sabbath’s Paranoid, Metallica’s Master of Puppets. We want to hold one artists work in our hands and read it all the way through in the order he or she intended, just like donning our headphones and laying back with Exile on Main Street kicking in.

- No avant garde crap. Sometimes I’ll recommend poetry that looks experimental (like e. e. cummings, who was so experimental that he decapitated the capitalisation in his name), but I’ll never excuse, promote, or feign to enjoy or respect the stuff that regularly turns up in The Paris Review. I won’t be joining any ‘boycott all straight white male authors’ bookclubs, of which so many fans of modern poetry seem to be a part.

- Only good stuff. In single malt whiskey terms, I’m serving you glasses of Yamazaki. Top shelf. Mature. Full-bodied. Rich. We’re going to get steaming drunk together.

- You’re going to kick it back to me. If you accepted my glass of fine scotch and it went down well, the brotherly thing to do is to let me know. What did you like the most? Tell me your favourite poem from the collection. Or, if you didn’t like it at all, tell me that too. We’re developing tastes here. I’ll try my best to only deliver the good stuff, but everyone’s palate’s different.

Poetry Pick of the Week:

The Whitsun Weddings (1964) by Philip Larkin

Larkin’s not the sexiest poet in the world.

He’s no rebellious Rimbaud or brooding Byron. He was bespectacled and bald and looked every bit of his profession: a librarian for the public library.

His choice of topic matter – or Muse – was not sexier either.

There were no dead soldiers with bullet holes oozing blood à la Rimbaud, no dark gothic legends à la Byron.

John Betjeman put it best when he described Larkin as the “John Clare of the building estates”.

Despite his unsexy appearance or subject choice, I would argue that Larkin is sexy.

Few poets are quite as evocative, or as skilled with sound, or able to bloat the text with vivid phrase after vivid phrase that not only conjures an image that unmistakably gets to the heart of the nature of the thing being written about, but also feels heavy and full in your mouth.

I could conduct an hour-long lecture on just two words in a Larkin poem.

But what two words would they be?

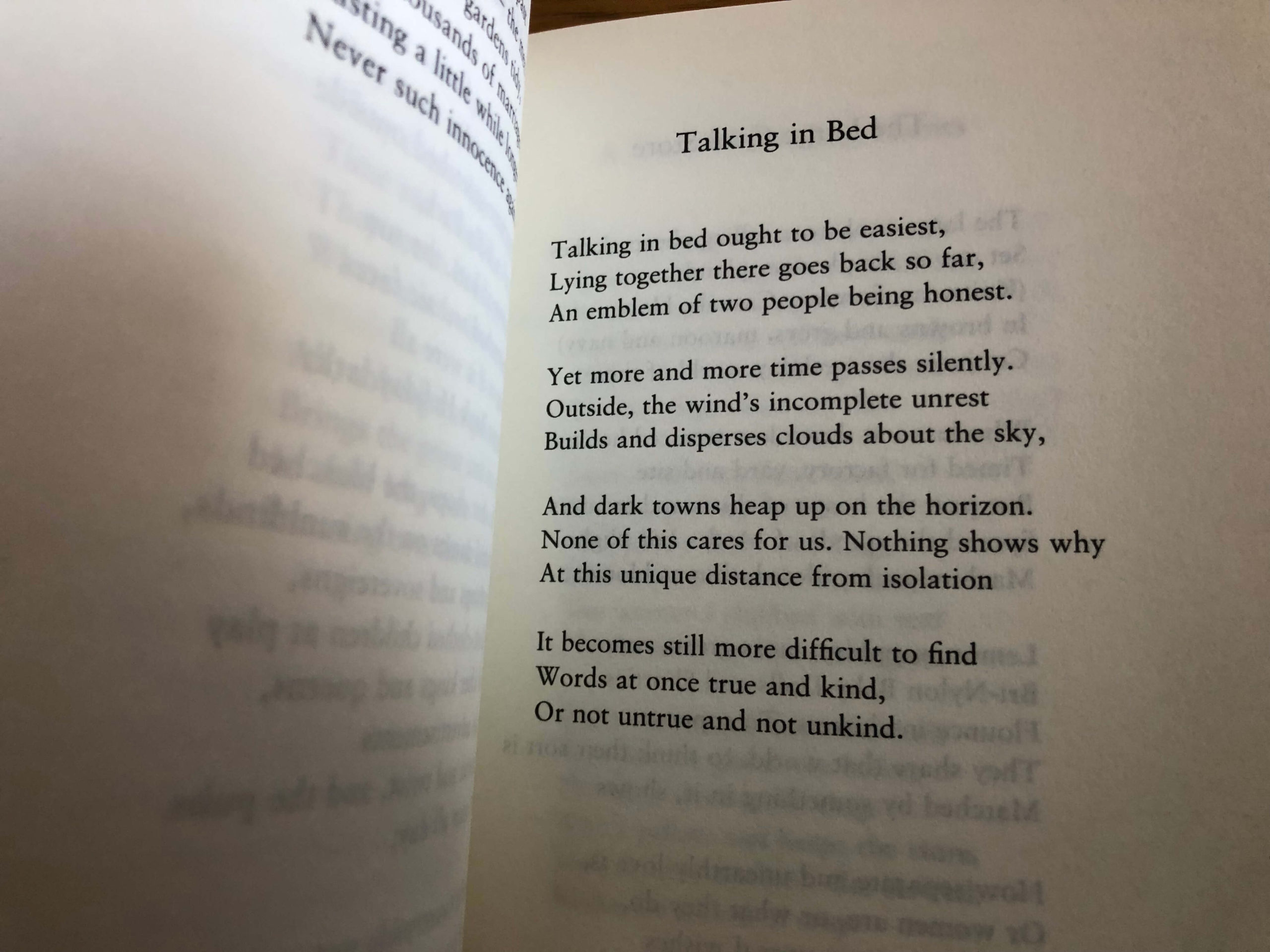

Would they be ‘Loneliness clarifies’ in the first poem to kick off this volume, ‘Here’? Would I try to argue that the two words that end of the poem ‘Home is so Sad’, the simple ‘That vase’, are the most perfect encapsulation of the feeling of time passing ever penned in the history of poetry? Or perhaps I’d pick apart the double meaning of ‘Lying together’ in Larkin’s ‘Talking in Bed’.

And that’s just studying two words. If I allow myself three words, I’d likely go for ‘Closed like confessionals’ from ‘Ambulance’. Wait, no. I’d go for ‘supine stationary voyage’ from ‘An Arundel Tomb’. Heavens, that’s a masterpiece of a poem. How could I choose just three words from that one?

The thing you’ll find with Larkin is, if you allow yourself to take your time and savour every line and let the poems work on you, you’ll have your breath taken away so forcefully you won’t even realise a tear has begun to stream down your face.

Few have so perfectly captured the human condition like Larkin. Almost no one has rendered the mundane as beautifully as him. And he is but one of a handful of poets that I trust will offer me something different, something prized, something poignant every time I come to him.

My favourite poems in The Whitsun Weddings are ‘An Arundel Tomb’, ‘Here’, ‘Ambulances’, ’Mr Bleaney’, ‘A Study of Reading Habits’, ‘Talking in Bed’, and ‘Days’.

They work in isolation as masterpieces, but reading them as part of their original volume adds an extra depth and vigour, one which I want you to enjoy.

If this is your first time reading Larkin, I envy you.

The Whitsun Weddings is Larkin’s fourth published work of poetry in an oeuvre of five volumes. They’re all superb, but my personal favourite is The Whitsun Weddings.

You can read The Whitsun Weddings here.