Many extol the virtues of reading, but few teach you how to read effectively.

Reading challenges abound online where quantity is the measure of success.

Read-a-book-a-week challenges. Read a hundred books a year!

But where are the calls for the most rewarding style of reading of all – deep reading?

For the large majority of people, reading only accentuates one’s ignorance.

This is because they fall prey to thinking quantity the best measure of one’s erudition.

They collect books like baseball cards and deem a speedy glossing sufficient criteria to say they’ve read a book.

Of course, some books are designed to be inhaled. But not the great books.

Freedom is knowing half a dozen books well.

Depravity and delusion is feigning to know two dozen a year intimately.

But how does one read deeply?

How do you suck the marrow out of books the way Thoreau wished to suck the marrow out of life?

I have my methods, but I’m not so stubborn as to ignore the methods others propose. Especially when they come from one of the greatest essayists who has ever lived: Michel de Montaigne.

How to read books like Montaigne.

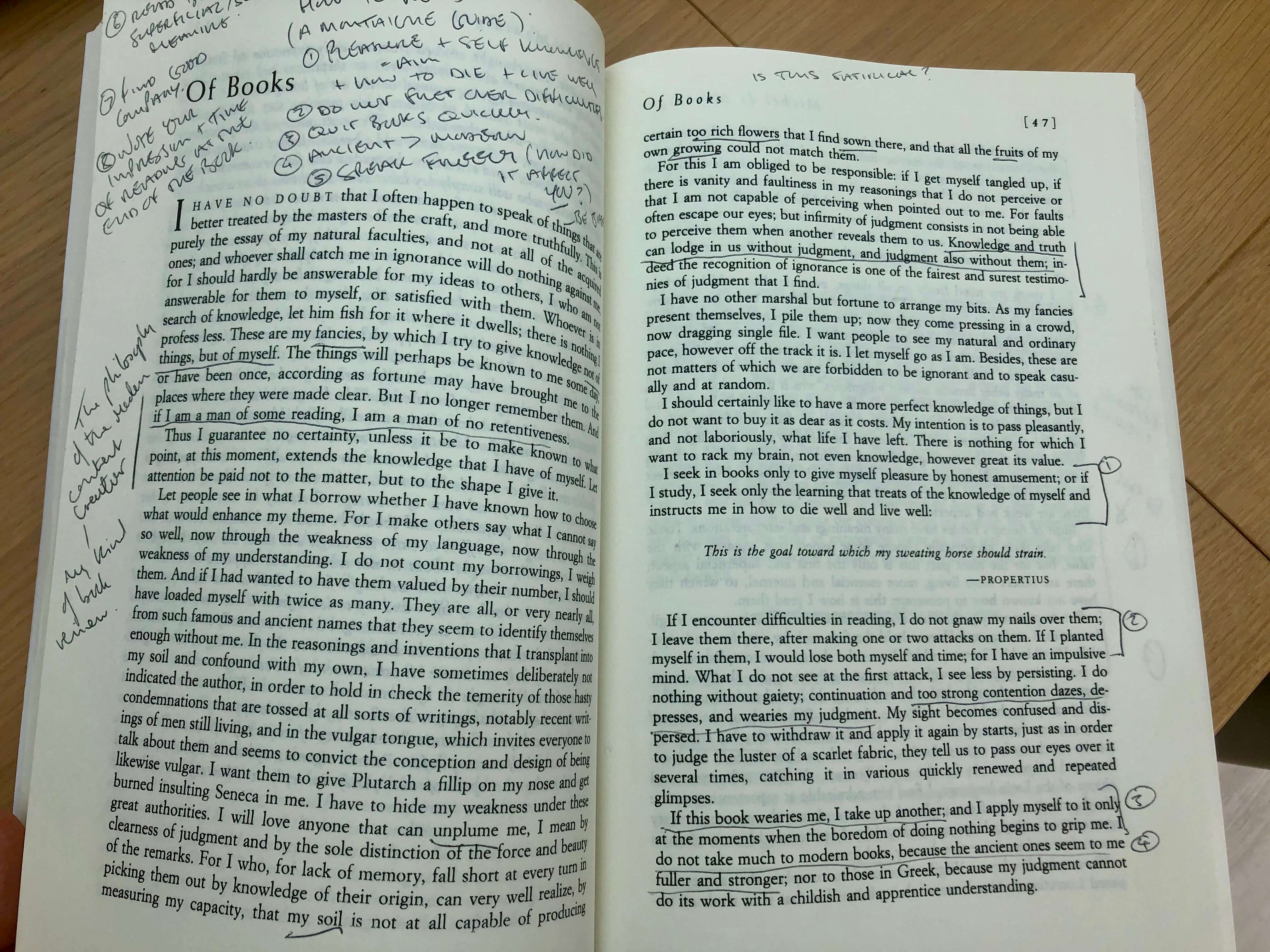

It was by virtue of reading Montaigne’s essay ‘On Books’ that I came to add a new set of valuable deep reading principles to my philosophy.

Here are eight ways you can read deeply like Michel de Montaigne.

1 – Speak freely and be biased – how did the book affect you?

I believe the best way to truly understand a book, or understand yourself better through a book, is by writing book reviews of everything you read.

These reviews don’t have to be long. And they certainly don’t have to be professional, whatever that means.

Many trip themselves up at the prospect of writing a book review. The phrase alone drums up images of snore-filled classrooms. But book reviews are not supposed to be some grand final say on what a book really means.

The best book reviews are the flawed books reviews, the reviews that reveal the essence of the reviewer.

When you read Frankenstein, don’t talk to me about the cruelties of man against nature. Don’t explore themes of playing God. Don’t try to read the text autobiographically. Unless those things directly move you personally right now.

Read the book as a mirror that reveals your nature at this moment.

If you’re going through a divorce and you read Pride and Prejudice, that book is about your separation!

Did Austen write the work with that theme in mind? Certainly not. But does that defy you finding some truth on that matter in this tome? Absolutely not.

Orwell recapitulates Montaigne’s philosophy in his essay ’In Defence of the Novel’ when he calls for more amateur reviewers.

There is power in being an amateur because you bring ideas to each work that academics set in their ways couldn’t entertain in a million semesters.

Here’s what Montaigne says:

I speak my mind freely on all things, even on those which perhaps exceed my capacity and which I by no means hold to be within my jurisdiction. And so the opinion I give of them is to declare the measure of my sight, not the measure of things.

Montaigne goes on by drawing upon his “distaste for Plato’s Axiochus” as an example of this philosophy.

Surely one cannot call oneself learned if they fail to find power in Plato?

Montaigne counters this by saying that the best defence against this is to recognise your weakness. Perhaps you do not know what the academics know about this work. But this doesn’t matter.

What matters is your honest evaluation and personal response to the work.

It’s perfectly acceptable to dislike great works.

Be like Montaigne. Here is his philosophy when reading a book:

These are my fancies, by which I try to give knowledge not of things, but of myself.

This has long been my philosophy when reading deeply and it’s this approach that makes my book reviews some of the best in the world.

I say that not with ego, for I claim no superior reasoning or rhetorical ability. All I mean is I am fiercely honest in my appraisal of great books – more so than you could ever hope to find in the more polished reviews of The London Review of Books or The New Yorker.

2 – Make pleasure and self-knowledge your aim. Seek to learn how to die and live well.

Most read the great books wrong.

Many will avoid or abandon great works of literature for fear of boredom or confusion. But this mindset comes from being weighed down by assumptions that do not serve you!

Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment or Homer’s Iliad both suffer from a reputation that precedes them so heavily that many cannot fathom the idea of understanding them, let alone enjoying them, before they’ve even arrived at the first page.

Dispense with the idea that the great books are difficult or boring.

Yes, they are hard work. But this is a pleasurable work. At least it should be if you read them the right way.

Take Montaigne’s philosophy of reading when approaching your next seminal work:

I seek in books only to give myself pleasure by honest amusement; or if I study, I seek only the learning that treats of the knowledge of myself and instructs me in how to die well and live well.

I love how Montaigne orders his learning priorities – learning how to die well comes before learning how to live well.

Think about that for a moment. We’re on a journey from cradle to grave, drawing ever nearing to oblivion, so surely every moment spent living is an opportune moment to learn how to die.

As Robert Louis Stevenson says:

We advance in years somewhat in the manner of an invading army in a barren land.

We must learn the tactics and strategies of such an advance!

But how do you find pleasure by honest amusement in intimidating tomes by writers like Homer, Dante, and Shakespeare?

First, it’s all about how you approach these works. Kurt Vonnegut’s advice is beautifully conceptualised in his writing to his students advising them how to read a collection of short stories:

Read them for pleasure and satisfaction, beginning each as though, only seven minutes before, you had swallowed two ounces of very good booze.

You can also follow Mortimer Adler’s advice on reading imaginative literature:

Become at home in the world of the book you’re reading. Become one of the population. Systematically befriend the characters. Live alongside them.

This is how I managed to get great pleasure from Homer’s Iliad recently.

I placed myself on the shores of Troy alongside Agamemnon, Achilles, and Menelaus. I felt the sand between my toes, the weight of a bronze spear in one hand and shield in the other, the burning fury within my chest.

3 – Do not fret over difficulties.

If reading with a dictionary beside you seems too laborious (and I would agree), then don’t do it!

We can understand much more than we give ourselves credit for.

We don’t need to look up every stray fact or unknown word that confuses us.

We can still feel the beat and pulse of life in the rhythm of the words.

Allow the current of truth and beauty to carry you along.

If you wish to explore beyond the text more, do so as long as you are compelled to. But if looking stuff up is an obstacle to getting you to read, remove the obstacle!

As Montaigne says:

If I encounter difficulties in reading, I do not gnaw my nails over them: I leave them there, after making one or two attacks on them. If I planted myself in them, I would lose both myself and time; for I have an impulsive mind. What I do not see at the first attack, I see less by persisting. I do nothing without gaiety; continuation and too strong contention dazes, depresses, and wearies my judgement.

If such a style of reading is good enough for one of the greatest essayists who ever lived, then it’s good enough for me and you.

4 – Quit books quickly.

Life’s too short to persevere with books that bore you.

Of course, I would personally argue that one needs to make the distinction between difficulty and boredom. But if you have given a book a solid effort and you find such efforts aren’t rewarded, move on to something that does reward you.

Here’s how Montaigne puts it:

If this book wearies me, I take up another; and I apply myself to it only at the moments when the boredom of doing nothing begins to grip me.

5 – Ancient > modern.

It’s true that books being written today will someday become classics. Though it’s hard to see when you’re in the thick of a time what will transcend the era you’re in and what will be left behind forgotten.

I do love a good modern book, but I know that time has already tested the fortitude of great books. The fact that they endure and comprise canons means they have something to offer, something that speaks to the essential nature of humanity.

I put my trust in time. And so does Montaigne:

I do not take much to modern books, because the ancient ones seem to me fuller and stronger.

6 – Read beyond superficial and surface interpretations.

This point is an addendum to Montaigne’s, Orwell’s, and my imploring for you to access the personal.

In Oxford, they told us that this is how you thought of a great thesis:

- Think of the most humdrum, boring, banal, matter-of-fact thesis possible.

- Think of the most wild, wacky, off-the-wall thesis that would never be accepted.

- Put yourself bang in the middle of those two poles.

The same works when it comes to reading books.

Here’s Montaigne weighing in:

Most of Aesop’s Fables have many meanings and interpretations. Those who take them allegorically choose some aspect that squares with the fable, but for the most part this is only the first and superficial aspect; there are others more living, more essential and internal, to which they have not known how to penetrate; this is how I read them.

Let’s do this now.

Think of the fable of the tortoise and the hare. The allegorical message that has endured through time is that “slow and steady wins the race”.

But can we be like Montaigne and find a different, more essential interpretation?

What if the hare is the true victor of the story? What if the finish line is death and the tortoise, unchanging in character or habit all of his life, reaches the grave on a steady trajectory? What if the hare follows the true rhythms of nature, speeding and then resting, and so achieves more longevity?

What more interpretations can you think of?

7 – Find good company.

When Montaigne talks about his favourite writers (like the Roman poet Lucan), he talks about how he enjoys their company.

This is how you should think of books.

You are in conversation with another.

Imagine that you are physically in the company either of the writer or their characters.

How one can ever feel loneliness when there is always a writer with whom you can intimately pass the time is beyond me.

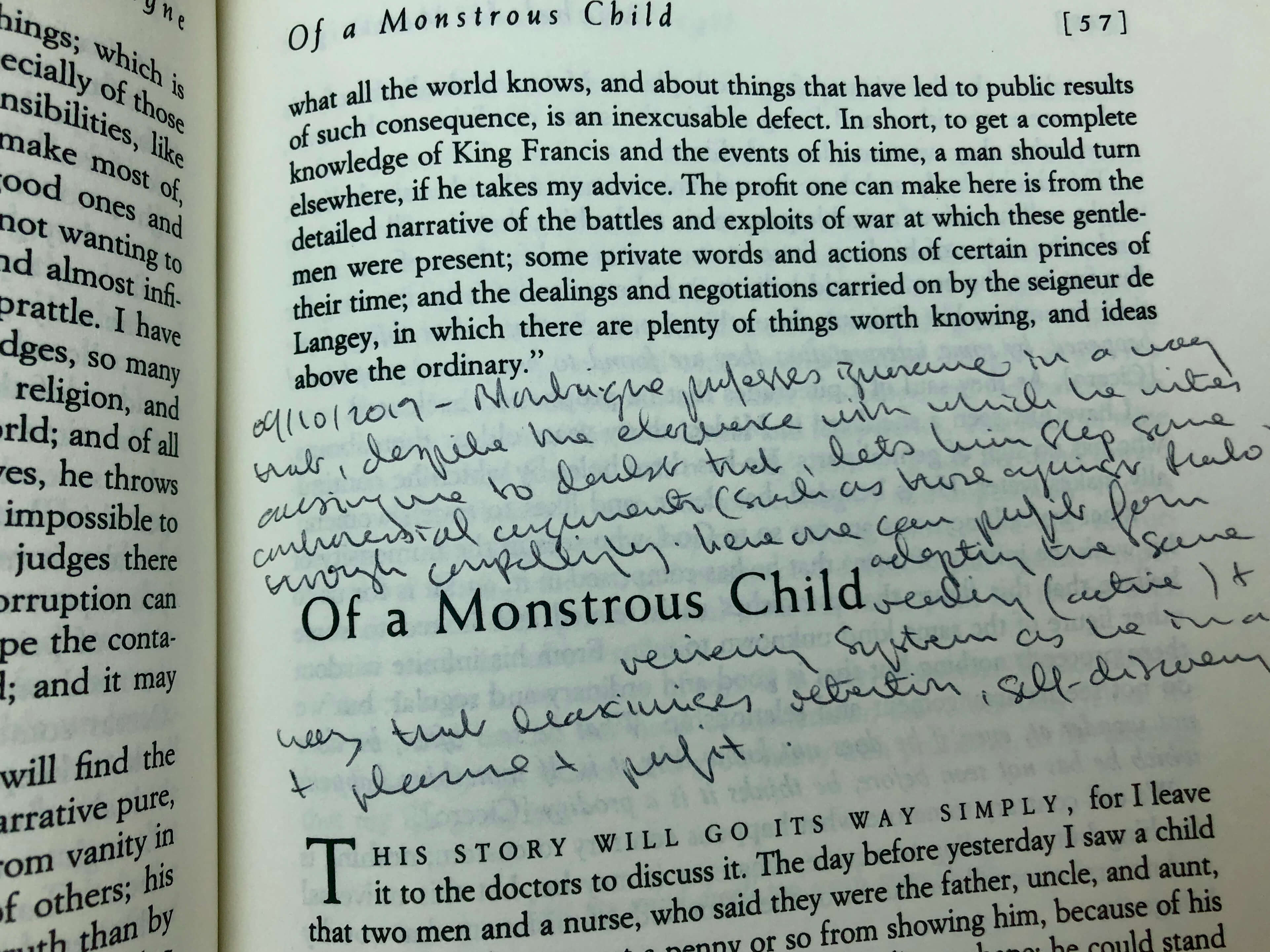

8 – Note your impressions and time of reading at the end of the book.

This is one of my favourite new additions to my active and deep reading routine.

I have always scribbled furiously in margins, made notes, underlined and circled, written book reviews, but it’s only lately that I have adopted this lovely little technique of improving retention (emphases my own):

To compensate a little for the teacher and weakness of my memory, so extreme that it has happened to me more than once to pick up again, as recent and unknown to me, books which I had read carefully a few years before and scribbled over with my notes, I have adopted the habit for some time now of adding at the end of each book (I mean of those that I intend to use only once) the time I finished reading it and the judgement I have derived of it as a whole, so that this may represent to me at least the sense and general idea I had conceived of the author in reading it.

Montaigne then goes on to show some examples of how he does this with different books, which you can read in this fantastic anthology of essays: The Art of the Personal Essay.

I immediately put this technique to use, put the date underneath Montaigne’s essay and scribbled a paragraph that worked as a synopsis of what I had just read and what I felt about it. This little snippet would work perfectly if I needed to persuade someone quickly to read Montaigne’s essay, but works even better to solidify my impressions of the work.