We hear it all the time. “That picture’s sublime.” “That doughnut was freaking sublime.” “Darling, wasn’t that orgy simply sublime?” But what does “sublime” really mean? Is it really just an adjective for “very good?” Well, not really… Let’s take a quick look at what sublime really means in the context of Romantic poetry. And by ‘Romantic poetry’, we’re not talking about the sappy stuff that teenage girls write in pink ink. We’re talking about the period of time in literature from around 1800 to 1850. You know, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Blake, and all that good shit. Sublime shit.

What the heck is sublime?!

The best definition of “sublime”, and one that influenced many of our favourite Romantic poets, comes from a bloke named Burke. Edmund Burke nailed the definition in his work A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757). It sounds like a hefty tome but it’s actually a really enjoyable read and one of the few books I sleep with under my pillow (along with my dagger and a piece of the true cross).

My man Burke argues that the highest degree of pain is more affecting than the highest degree of pleasure. The sublime then arises from a confrontation of ‘danger or pain’, as long as they are at ‘certain distances’ and with ‘certain modifications’, at which point it is regarded as ‘delightful’. Here’s Burke’s definition of the sublime. Pay particular attention to the last clause:

‘Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling.’

The reason that art is able to create and communicate the sublime is because it is at the distance necessary for ‘terrible objects’ to be delightful instead of dangerous.

A wild animal in a painting or poem is able to inspire fear and awe is elicited on the part of the viewer or reader because they can appreciate the danger and power it possesses without being susceptible to harm (other than the occasional paper cut perhaps).

Burke attributes the satisfaction one gains from sublime art to the consideration that what we are observing ‘is no more than a fiction’ but the ‘nearer it approaches the reality, and the further it removes us from all idea of fiction, the more perfect is its power’.

Burkey-boy categorizes the sublime in various ways. First and foremost is ‘terror’, which is described as the ‘ruling principle of the sublime’.

William Blake and the Sublime

Lets focus on a Romantic poem that everyone knows very well. ‘The Tyger’ by Blake is an example of a sublime Romantic poem that produces terror in its subject matter. Blake conveys this great fearful presence is by repetition in the first line: ‘Tyger, Tyger’. This repetition leads to an image which is as heavy as a tiger should be. The first line could also be seen as evoking the stuttering and fearful words of warning that one may achieve upon seeing such a wild animal.

Blake continues to evoke the sublime in ‘The Tyger’ with effects that Burke terms ‘obscurity’ and ‘power’. Burke argues that the evil we know is easier to confront than the evil we do not know.

Obscurity is terrifying and, therefore, imitation of it lends itself to the sublime. He uses Milton’s description of the shapelessness of Death in Paradise Lost as an example. The sublime object doesn’t always have to induce terror; it could display strength and power instead:

‘We have about us animals of a strength that is considerable, but not pernicious. Amongst these we never look for the sublime: it comes upon us in the gloomy forest, and in the howling wilderness, in the form of the lion, the tiger, the panther, or rhinoceros’.

Forests are often a setting for the sublime in Romantic poetry. The motif of the forest unites the ideas of power and obscurity together. Because the animals that live in the forest are obscured they are more terrifying. Because they are more terrifying they are more powerful. Their power also comes for the advantage of being hidden. They can take one by surprise.

Wordsworth describes the forests in The Prelude (1850) as being ‘unapproachable by death’ (Book VI, l.466). The forests and their inhabitants are so fearsome that death itself, the ultimate source of fear, cannot approach that envrionment.

The forests obscure because they are dark but Blake’s tiger, stalking the ‘forests of the night’, manages to terrify and attain the sublime due to it being simultaneously obscured and illuminated. When Blake describes the tiger as ‘burning bright’ he is achieving the sublime in several ways. Initially he is describing the orange sheen of the animal’s coat.

Burke says that intense light or intense darkness can both have the effect of the sublime and a ‘quick transition from light to darkness, or from darkness to light, has yet a greater effect’. In having the brightness of the light contained within a naturally dark environment Blake is able to alternate the images of light and dark to create a more affecting image overall that leads to the sublime. The tiger’s brightness also acts metaphorically to symbolise its power; the unknown and vast interior of the forest has momentarily been diminished and dwarfed by the brightness of the tiger. The fact that the tiger is described as ‘burning’ also acts to suggest its capability to destroy.

The obscurity of Blake’s tiger can be seen in the poem’s metrical scheme which compliments and reinforces the idea of obscurity inherent in the stripes of the tiger, obscuring its whole, and the trees of the forest, which act to obscure the tiger.

The first stanza begins regularly with trochaic tetrameter (that’s right, you never thought I’d being busting out the Greek terminology,did ya?) and clipped syllables in the final foot until the fourth line becomes iambic tetrameter. The second stanza returns to the initially erected (lol) metrical structure but the seventh and eighth lines do not have the final feet clipped and are instead bestowed with feminine endings. Alternations such as these continue throughout the poem to create a syntactical metaphor for obscurity, mirroring the stripes and trees of the tiger and forest. The poem’s metrical scheme also evokes the idea of great power.

The content of the poem can barely be constrained to the forms and conventions of the art and, likewise, the tiger can barely be contained by the forest. Blake asks ‘What immortal hand or eye | Could frame thy fearful symmetry?’

Boom. Blake’s done. Him and Tigger are both sublime motherfuckers. Who’s next?

Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Sublime

Let’s take a look at the sublime in another famous Romantic poem by everyone’s favourite smack-head and loving father Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798).

When the ancient Mariner begins to tell his tale to the ‘Wedding-Guest’ he initially ‘holds him with his skinny hand’ but quickly progresses to hold him with his ‘glittering eye’ too. Due to the Mariner’s small physicality but power of gaze, his dominance over the wedding-guest is suggested to be an other-worldly one which acts to instil the idea of terror and the unknown.

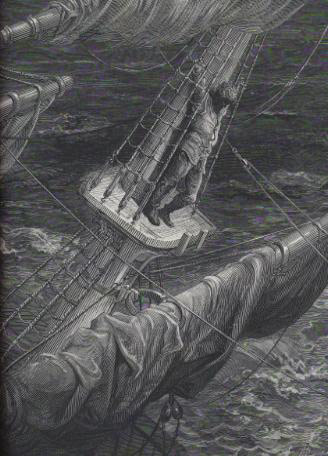

Gustave Doré’s wood-engraved illustration of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner really exemplifies the sublime.

The Mariner has the ability to dominate (giggity) and make someone subservient, ‘like a three years’ child’, which reinforces Burke’s idea that pain, intricately linked to the sublime, is ‘always inflicted by a power in some way superior, because we never submit to pain willingly’. That’s right, the sublime is all about being bent over and shafted against our will.

Coleridge suggests the wedding-guest to be utterly powerless against the ancient Mariner when he details that he ‘beat his breast, | Yet he cannot choose but hear’. So far as the reader is reading this he is aligned with the figure of the wedding-guest who is powerless to resist the Mariner’s tale and in a similar way the reader feels powerless to resist the tale as well.

Power, here, is again mixed with obscurity. In the Mariner’s tale, the pervasive power of the ice surrounds and invades the Mariner’s ship, obscuring the ‘shapes of men’ and encompassing everything: ‘The ice was here, the ice was there, | The ice was all around’ (ll.59-60). Power is further asserted by the noise of a ‘STORM-BLAST’ and the noise of the ice as it ‘cracked and growled, and roared and howled’.

The sublime appearance of nature continues to be raised as Coleridge displays its power to obscure even further. The ship is ‘hid in mist’ and so removed beyond landscapes and horizons that objects come from far away and are initially difficult to decipher: ‘A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist!’. In several instances, it is the sound of words that emphasises the sublime:

‘The fair breeze blew, the white foam flew,

The furrow followed free;

We were the first that ever burst

Into that silent sea.’ (ll.103-6)

Burke makes examples of the noises of ‘vast cataracts, raging storms, thunder, or artillery’ to explain that excessive noise is ‘sufficient to overpower the soul, to suspend its action’, ‘fill it with terror’, and awake a ‘great and aweful sensation in the mind’.

Similarly, here Coleridge evokes the raw power of nature by utilising language that sounds loud and powerful. Although technically tetrametric (boom, did it again), Coleridge manages to condense six stresses into the first line. The stresses are divided by the caesura and split into two groups of three resulting in a heavy utterance that takes time to say. Combine this with the internal rhyming and plosive alliteration, ‘breeze blew’ and ‘burst’, and the fricative alliteration, ‘fair’, ‘foam flew’, ‘furrow followed free’, and ‘first’, and the sounds of oppressive winds and violent sea spray are conjured up.

Double boom. First Blake, now Coleridge. Knocking these sublime motherfuckers outta the park. Next!

William Wordsworth, the Sublime, and the Beautiful

Let’s take another super popular example and look at the work of a man so skilled with words that he put the word ‘word’ in his freaking name. Talk about commitment to craft. It’s Willy Wordsworth and ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’.

Combining power and obscurity, Romantic poetry’s focus on the natural world can see a creation of the sublime in what Burke calls ‘vastness’ and ‘magnitude’. But in Wordsworth’s ‘Lines Composed a Few Miles Above Tintern Abbey’, the creation of the sublime is initially subservient to the creation of the beautiful (which Burke’s book goes into more detail about).

The sublime can subtly be seen in the imagery of ‘steep and lofty cliffs’ and the suggestion of mountains from descriptions of waters ‘rolling from their mountain-springs’. It is these natural wonders, in their vast measurments and magnitude of stature, that reach the sublime. Despite this, the ideas that Burke would categorise as “beautiful”, rather than “sublime”, are initially dominant in Wordsworth’s scene.

Whilst Burke defines the sublime as arising from pain, he defines the beautiful, in contrast, as that arising from pleasure. The aesthetic qualities that are seen to give pleasure and contribute to the beautiful are to be ‘comparatively small’, ‘smooth’, possess a ‘variety in the direction of the parts’, have their parts ‘melted’ into each other, have a ‘delicate frame’, and to have ‘clear and bright colours’. Due to the height at which Wordsworth is contemplating the scenery, the size of each natural wonder is diminished and changing and varying topography can be seen clearly, adding to its beauty:

‘These plots of cottage-ground, these orchard tufts’ (l.11),

‘These hedge-rows, hardly hedge rows, little lines | Of sportive wood run wild’ (ll.15-6).

In these lines, the sounds composed are delicate ones; the velar and dental alliteration connotes small and beautiful imagery. Wordsworth recognises the scene as having ‘beauteous forms’ in contrast to the idea that the sublime is very often formless and obscure. He further reinforces the idea of describing the ‘sensations’ aroused as ‘sweet’ and describes feelings of ‘unremembered pleasure’ (say that phrase out loud… it’s fucking sexy).

Wordsworth eventually moves on to an ‘aspect more sublime’, noticing the difference between the sublime and beautiful, and praises ‘that blessed mood, | In which the burthen of the mystery, | In which the heavy and the weary weight | Of all this unintelligible world, | Is lightened’. The sublime is seen as a powerful force that is so strong that it can lighten the ‘weight’ of the ‘world’.

Wordsworth recognises the sublime to have the power to startle one into inaction and make one submissive to its dominance in a similar way to Coleridge’s ancient Mariner: ‘the motion of our human blood | Almost suspended, we are laid asleep | In body’. The submissiveness the sublime instills in one is suggested in Wordsworth’s passive construction, ‘we are laid asleep’.

And that is the power of the sublime. It lays us asleep, it awes us, it bends us over and takes us from behind without so much as a ‘how d’you do?’

Find out more about the sublime

If you want to know more about the sublime in literature and my childish and offensive reading of the great Romantic poets has left a bitter taste in your mouth that you desperately need to wash out… Why not pick up one of these books on the subject?

Burke, Edmund, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful

Mortensen, Klaus, The Time of Unrememberable Being: Wordsworth and the Sublime

Kant, Immanuel, The Critique of Judgement

Read some damn good Romantic poetry

Blake, William, Selected Poems

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, Selected Poetry

Wordsworth, William, The Collected Poems of William Wordsworth