The mark of a literary masterpiece is how thoroughly the concerns of its characters become your concerns.

Do you think of the novel’s characters as though they were real people?

Not wholly good, not wholly bad, but with dreams, desires, fears, and the ability to change – either towards decay and stagnation or towards God and salvation.

Do you read the words or do you feel breath and beating hearts?

Anna Karenina (1878) by Leo Tolstoy is, regrettably, my favourite novel because it is precisely that kind of masterpiece.

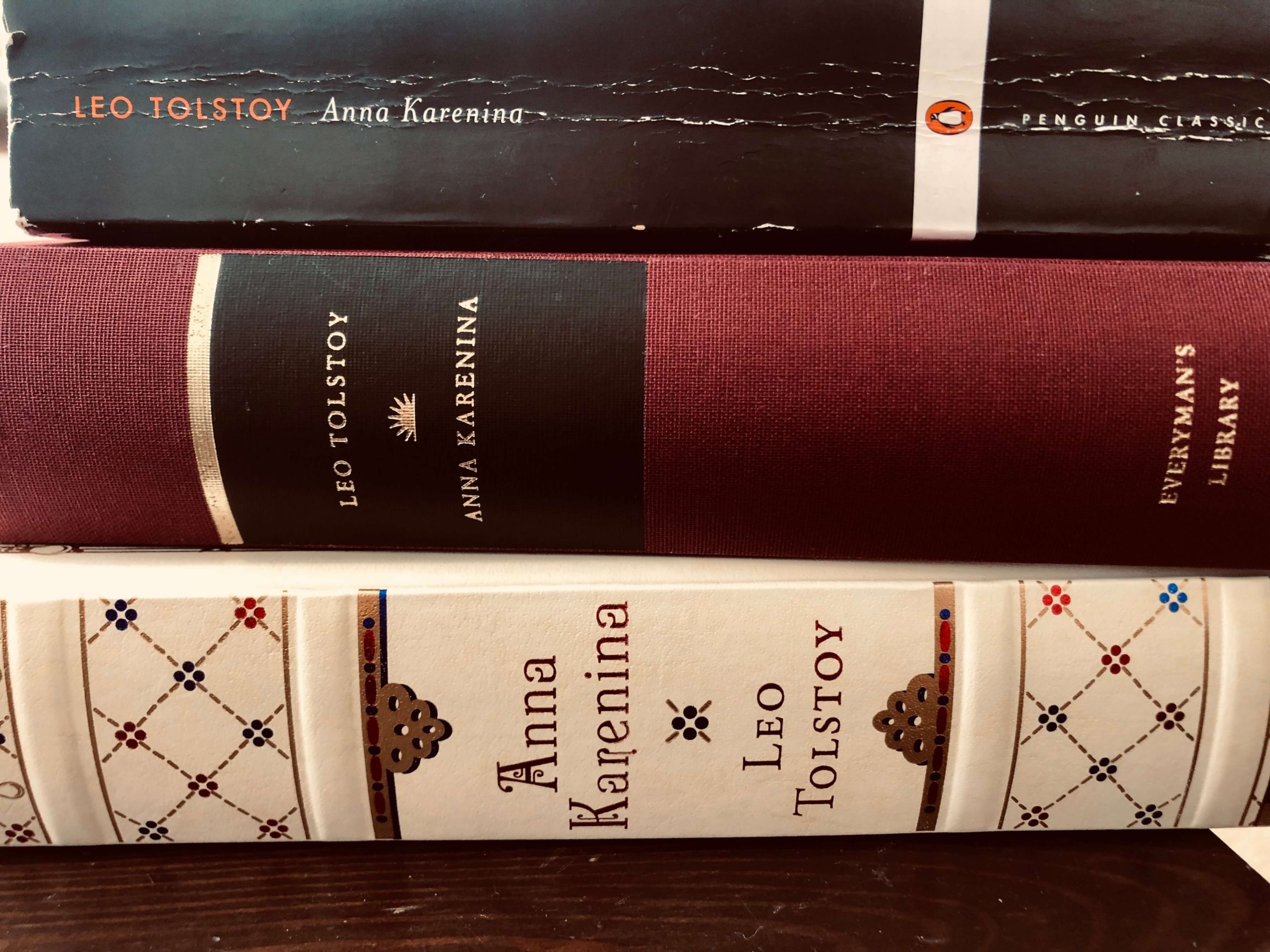

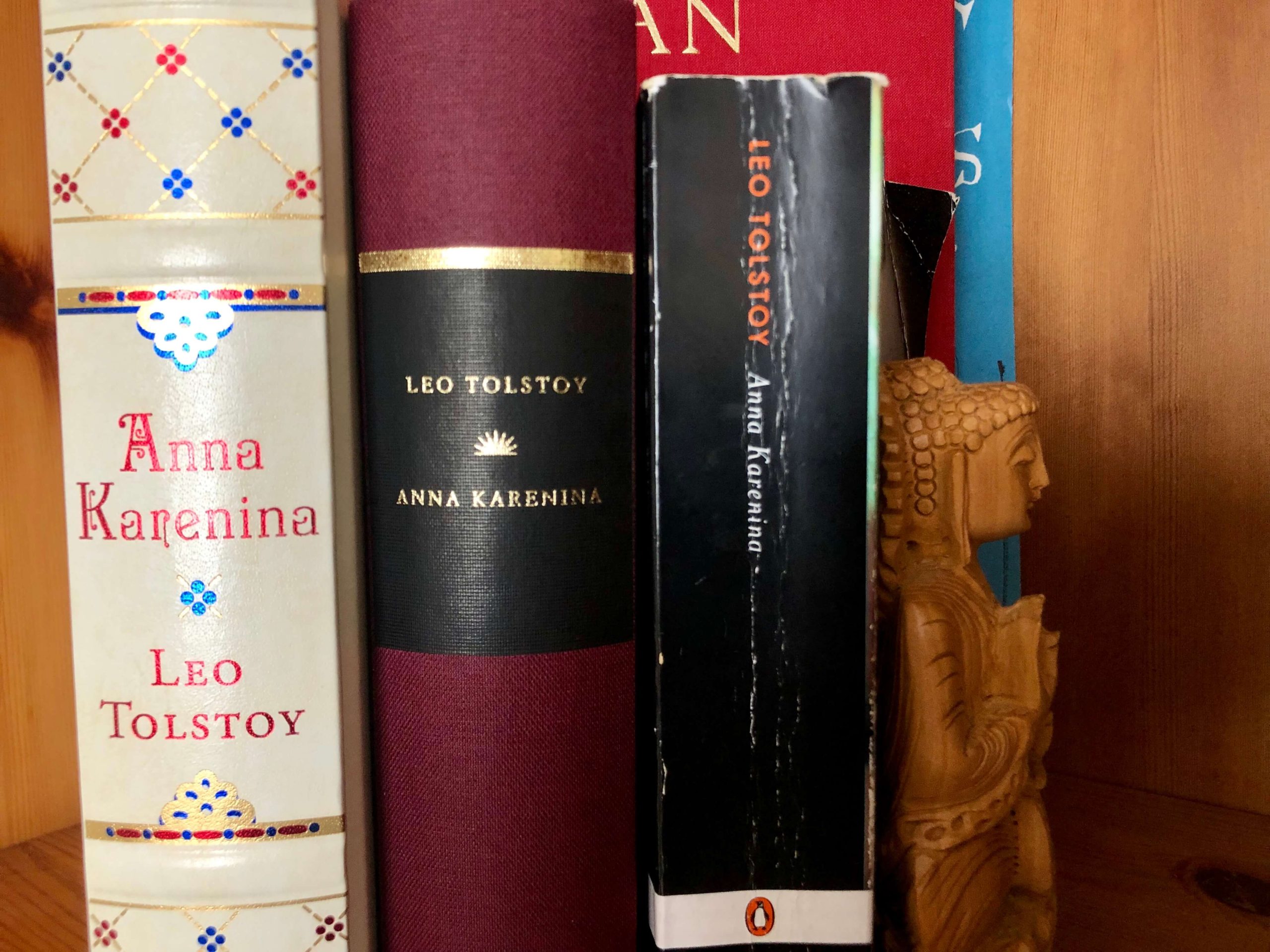

From left to right, editions of Anna Karenina: Constance Garnett translation, Aylmer and Louise Maude translation, Pevear and Volokhonsky translation.

I say regrettably because this was not a work that I inhaled. I left it for long periods of time gathering dust while I gallivanted with more exciting writers.

I grew bored and impatient while Levin spent a hundred pages proselytising, preaching, and sermonising about peasantry and agriculture in haystacks after the object of his affection, Kitty, scorned him.

I wanted to slap the self-righteousness, the smugness, and aristocratic privilege out of Count Vronsky, and felt hard done by my inability to break him the way he broke his horse, the way he broke Anna.

And the character whose name adorns the cover. Anna is not the central protagonist, and takes her time arriving by carriage into our lives, but we follow her plight nonetheless. Selfish, egocentric, narcissistic. She’s a mirror. A broken mirror. One held up to society, held up to her brother and wife, and held up to the real protagonist, Levin, who is a stand-in for Tolstoy himself.

I disliked, despised, even hated, and then, eventually, came to accept the characters.

But here’s the key: accept them as people, not as characters.

Because there is not one moment across the span of this epic double Bildungsroman in which the realness of Anna, Levin, Vronsky, Stepan, Kitty, Dolly, or Alexei is called into question.

You take each and every one of them so utterly and totally for granted as real psychological complex people, wonder why they did this or why they did that, judge them and question their morals (something Tolstoy, as God in his novel, never does), and ultimately come to know them better than you know the people in your own life.

Nabokov, in his Lectures on Russian Literature, ranked the great Russian writers in order. He made apologies to Dostoyevsky and proclaimed the top four, in reverse order, to be: Turgenev, Chekhov, Gogol, and then, finally, with him as the grand burning sun sitting at the centre of the solar system, Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy.

One need know nothing about Tolstoy’s personal life to enjoy his writing, though here are a few biographical peculiarities about the man, the writer of Anna Karenina, War and Peace, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, and the late great Harold Bloom’s favourite Hadji Murat that I find myself trying to reconcile with the works themselves.

The first is Tolstoy’s scorn for the novel.

Levin’s religious transformation throughout Anna Karenina was Tolstoy’s own, one that transcended him by the end of the novel – a novel, you might be interested to know, originally started as a short work after Tolstoy was witness to an adulteresses’ suicide by train trammelling and blossomed out to half-a-decade of artistic struggle.

By the time Tolstoy had finished Anna Karenina, he had vowed never to write another work, thinking the form to be a transgression against God. And perhaps it might. In the hands of a Maupassant or Sterne, it might be. But in the hands of a man who set the foundation for omniscient narration in the novel?

How much Tolstoy truly believed his art offended his God is up for debate.

He never wrote a long work of staggering beauty again, though he could not resist penning multiple novellas before his death at the grand age of eighty-two.

Another curious fact about Tolstoy is his hatred for Shakespeare. But I believe the Count did protest too much. Particularly in his most fervent damnation of King Lear, whose central archetype Tolstoy seemed to grow into.

What makes Anna Karenina one of the greatest novels ever written?

Is it the psychological complexity of the characters?

Is it the real sense of time passing?

Is it Tolstoy as God in the narrative?

Is it the treatment of society, education, love, jealousy, mental illness, men and women, spirituality, happiness?

Is it the mysterious compulsion the reader feels not only to question and examine the lives of those who people the novel in conjunction with their own but also to relive the story again and again in search of ever-broadening circles of comprehension?

Is it the fact that the novel makes you want to be a better person?

Perhaps all of this and more.

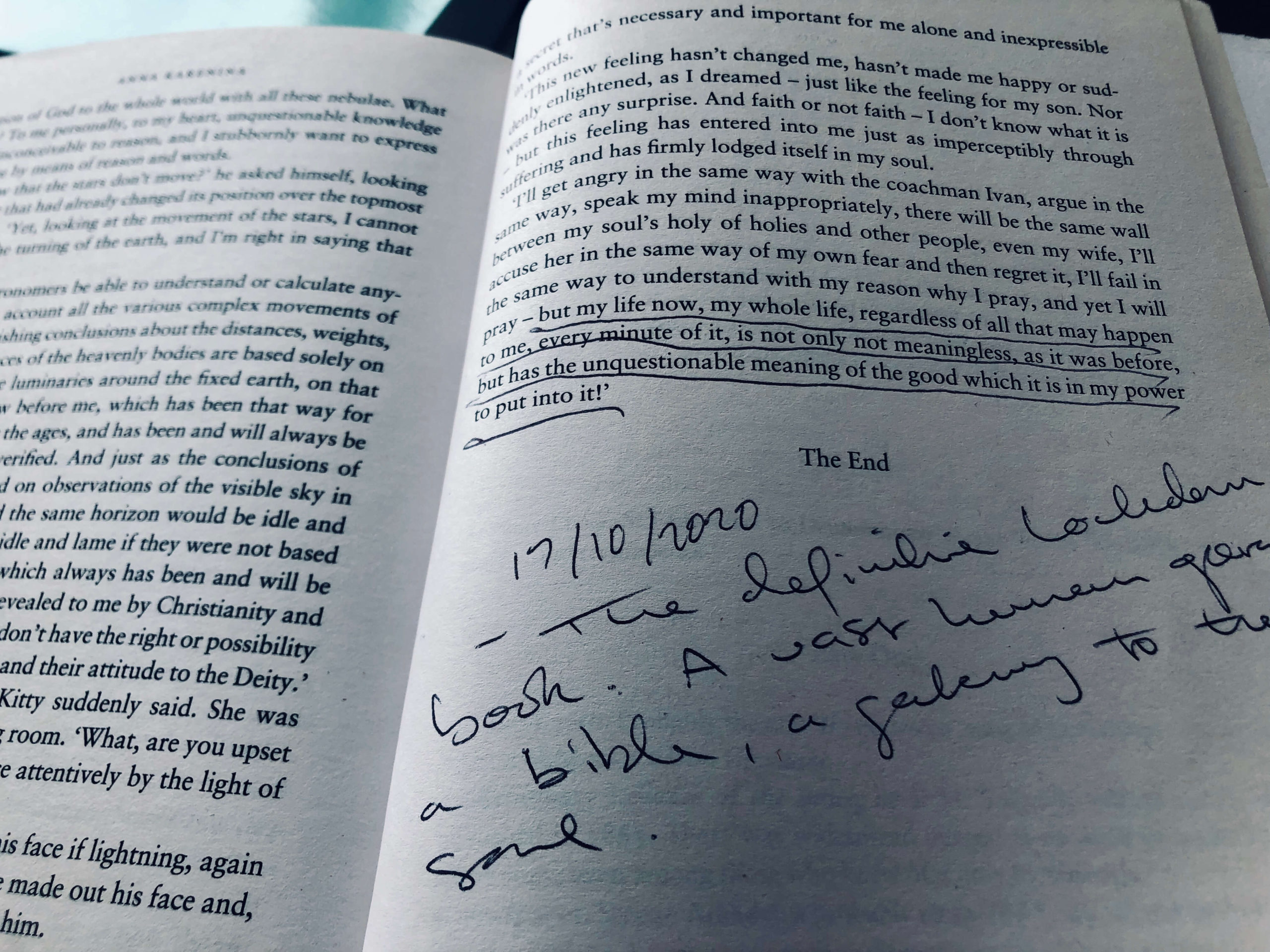

But especially because, by the time you reach the end of Anna Karenina, you realise that your life, your whole life, regardless of all that may happen to you, every minute of it, “is not only meaningless, as it was before, but has the unquestionable meaning of the good which it is in your power to put into it.”