Your first million words are practice.

You haven’t earned the right to be frustrated with your lack of creative success until you’ve clocked at least a million words of practice.

You might hit gold somewhere in the middle of those million words.

Your first novel might be a huge success.

But it’s not likely.

Show me an “overnight success” in any field and I’ll show you someone who put in 10,000 hours behind the keyboard, on the basketball court, in the music hall, in the kitchen, in the laboratory.

You know about Gladwell’s “10,000-hour rule” by now.

But did you know that rule has been disproven?

It’s not actually the quantity of hours that is the important factor in improving your craft.

It’s the quality of those hours.

Well…..

Quality AND quantity.

What the guitarist for Rage Against the Machine taught me about deliberate practice

In his Electric Guitar MasterClass, Tom Morello, guitarist for Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, and Prophets of Rage, has a lot to say about deliberate practice.

Practice has played a huge role in my life as a musician. I had literally zero natural ability on the guitar. I had to fight for ever single inch of my guitar playing. Later on, there were breakthroughs where creativity came easy, where I was able to move my fingers around the fretboard. But I promise you, and hear these words — I had zero natural ability. It was only through hours, and hours, and hours of practice that I was able to amass some sort of ability on the guitar.

The man responsible for some of the most famous riffs in rock is saying he had zero natural ability and it was only through practice that his skill became what it is.

Morello says that the three crucial building blocks to practice are:

- practicing every day

- playing with other people

- playing live

Now obviously he’s talking about the guitar here, but it doesn’t take much of a stretch to make these building blocks fit the craft of writing:

- write every day

- read and share with other people

- publish your work

Practice —> Feedback —> Adapt, Learn, Practice

Morello talks about how in high school a friend gave him the best advice when he was a beginning guitar player.

Practice an hour a day, every day, without fail.

The friend said if Morello was serious about wanting to play guitar, he would practice an hour a day, every day, without fail.

Morello took those words as gospel and he began practicing an hour a day, every day, without fail.

And after a couple of weeks his playing was noticeably better.

Jamming four hours on the weekend with friends, and then playing again in two weeks, then practicing one night for a half hour didn’t work.

Consistent practice worked.

Morello felt he was really behind in playing the guitar, starting at 17, but he made the commitment to practice an hour a day and found you can really catch up quick with an hour a day.

And if you can really improve with an hour a day…

What happens if you practice two?

After committing to two hours a day, Morello saw his playing ability grow exponentially.

And then he asked himself…

What happens if he practices four hours a day?

What if it was six?

And eventually it was eight hours a day, every day, without fail.

The “without fail” part is the most important part.

Morello says at college, when he was around the four hour a day mark, even if he had an exam the next morning, a fever of 101, and had finished studying at 1:00 AM, he would play the guitar until 5:00 AM.

Not 4:58 AM.

“Every day, without fail.”

He says that he practiced so hard, so consistently, and with such purpose in the summer sophomore year of college that when he came back home and showed his skills to his friends they couldn’t believe the transformation in just 8 months of time.

It’s amazing what you can accomplish in a year of consistent practice every day.

An hour a day for a year is 365 hours.

Not 10,000 hours.

But it’s the consistency of those 365 hours strung tightly together, and what you do in those hours, that will make your progress jaw-dropping.

You only need to do a quick YouTube search for “[Skill] + [1 year progress]” to find some amazing proof of this:

- 1 Year of Learning the Cello

- Guy learns to dance in a year (TIME LAPSE)

- Guy Plays Table Tennis Every Day for a Year

- Adult beginner violinist – 2 years progress video

- 5’7″ White Kid Dunks After 6 Months Of Training

Make a commitment to your craft.

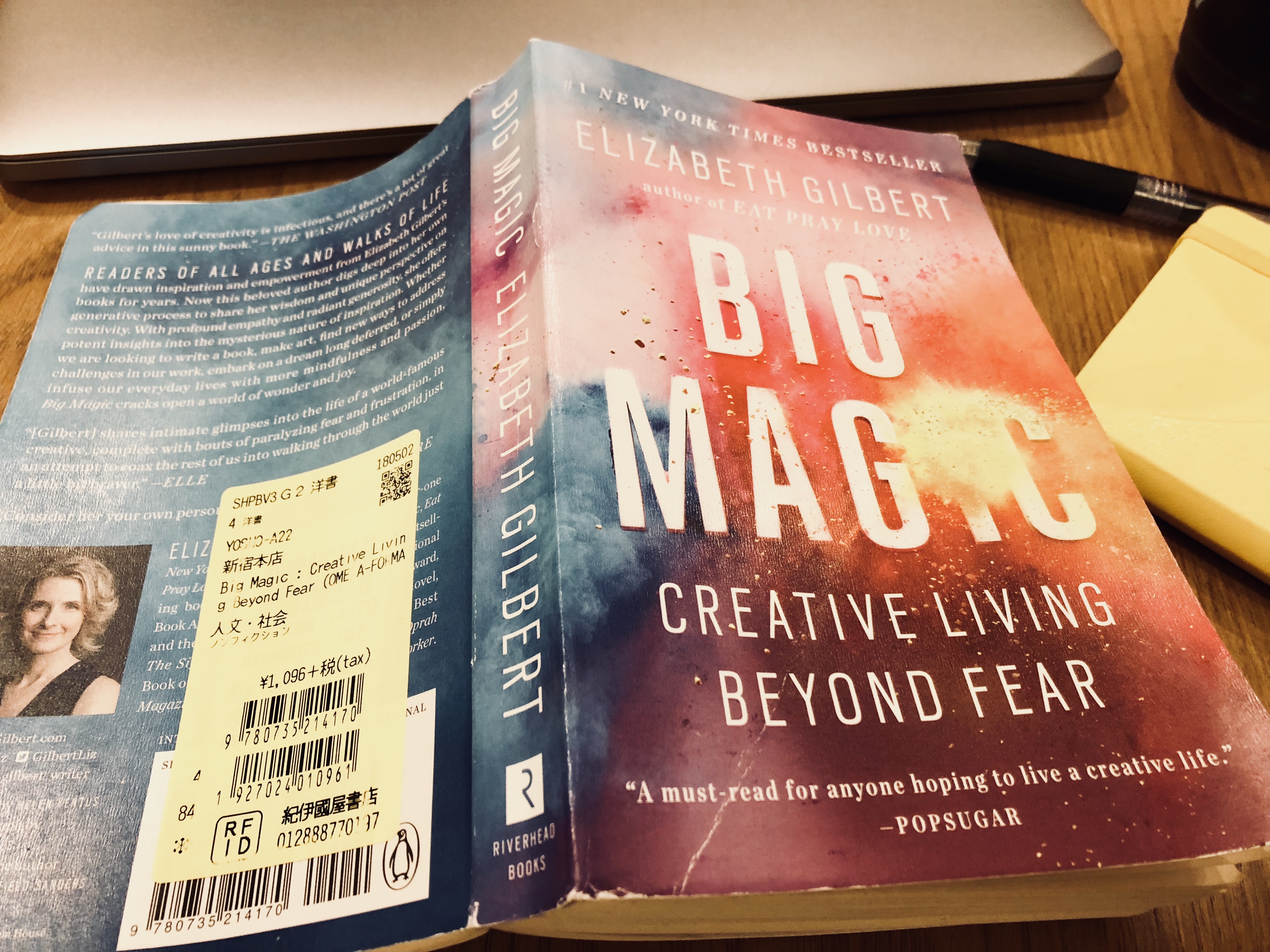

Morello’s iron-clad commitment to his practice reminds me of a similar commitment Elizabeth Gilbert made to her writing practice (which she talks about in Big Magic).

When Gilbert, of Eat Pray Love fame, was sixteen years old, she took vows to become a writer.

My vows were strangely specific and, I would still argue, pretty realistic. I didn’t make a promise that I would be a successful writer, because I sensed that success was not under my control. Nor did I promise that I would be a great writer, because I didn’t know if I could be great. Nor did I give myself any time limits for the work, like, “If I’m not published by the time I’m thirty, I’ll give up on this dream and go find another line of work.” In fact, I didn’t put any conditions or restrictions on my path at all. My deadline was never.

No deadline, no conditions, no pressure put on her craft.

That’s real commitment.

Saying, “If I’m not published by the time I’m thirty” is not real commitment.

This is what real commitment looks like:

Instead, I simply vowed to the universe that I would write forever, regardless of the result. I promised that I would try to be brave about it, and grateful, and as uncomplaining as I could possibly be. I also promised that I would never ask writing to take care of me financially, but that I would always take care of it – meaning that I would always support us both, by any means necessary. I did not ask for any external rewards for my devotion; I just wanted to spend my life as near to writing as possible – forever close to that source of all my curiosity and contentment – and so I was willing to make whatever arrangements needed to be made in order to get by.

Start with an hour a day.

A lot of writers swear by a quota.

Stephen King famously demands 2,000 words of himself a day.

A quota is great once you’ve got the habit solidified and you know what you’re doing.

But a quota can put some unnecessary stress on you in the beginning.

Dan Brown, in his thriller writing course, recommends a time quota.

That way, if you’re having a great day, you don’t stop merely because you hit your word count. And if you’re having a sucky day, no pressure, you can still hit your goal instead of labouring 8 hours for a word count that should have taken you an hour.

There’s also the question of quality.

A lot of writers use November to pound out 50,000 words for NaNoWriMo. But anyone who has followed NaNoWriMo will tell you that quality is often sacrificed in order to hit that word count.

So give yourself a time quota, make a commitment to keeping it, then scale it up Morello-style when you get used to it.

How do you structure your practice?

In his early guitar days, Tom Morello broke his practice down into four 2-hour blocks:

- Block 1: technique

- Block 2: theory

- Block 3: songwriting/experimentation/pure creativity

- Block 4: improvisation

In the technique portion of the practice day, Morello spent his time exclusively doing mind-numbingly boring exercises that would allow his fingers to move around the neck in different ways when called upon to do so.

Stuff like playing the same three notes with his second, third, and fourth fingers a hundred times in a row.

Boring, yes – but it was this kind of deliberate practice that allowed him to unlock his potential.

In order to play fast and get command of the instrument, you must play super slow and in time.

That’s deliberate practice.

The greats in every field do it.

- Ben Hogan used deliberate practice to win nine major golf championships.

- Jiro Ono used deliberate practice to become one of the greatest sushi craftsmen.

- Kobe Bryant, Mozart, Joe DiMaggio, and Picasso all utilised deliberate practice.

How does learning technique look in the context of writing?

Deliberate practice in writing works like this:

You go into each writing session knowing what you want to accomplish.

You sit down for your hour-session knowing what you want to work on.

James Scott Bell, in How to Make a Living as a Writer, says you can isolate seven critical areas of fiction writing:

- plot

- voice

- theme

- scenes

- dialogue

- structure

- character

By isolating them this way, you can design a self-study program specific to your needs. When I was a few books into my traditional publishing career, I had an editor tell me my plotting was strong but my characterizations were weak. So I set up a six month program for myself. First, I selected several of my writing craft books that dealt with characters. Next, I took out several novels that I’d read with truly memorable characters, and bought a few that I’d heard had the same. Finally, I set aside time for writing exercise. When I read about a technique or saw something that worked in a novel, I practiced it. I’d write practice scenes or sometimes single pages. And, of course, I’d apply what worked for me in my main writing projects. Does all this sound like a lot of work? Good, because it is.

This approach to deliberate practice in writing really shows the importance of feedback.

Not only do you need to clock your words and sit down to write every day, but you also need to start collecting rejection letters, shipping your works, sharing your work with friends and beta-readers, and going to workshops in order to get feedback.

Feedback tells you what you need to work on.

Show your work to ten different people and they all say the dialogue is weak?

Great, now you know you need to hunker down and deliberately practice dialogue.

See a Mamet play, experiment with a dictaphone, copy Elmore Leonard dialogue out by hand.

Dean Wesley Smith has this to say about the relationship between practice and feedback:

The learning never stops in this art form, and the moment you think you are “good enough” you are dead. I once had an interviewer ask me why I wrote so many media novels. My standard answer is, of course, that I loved the universes and the characters and the work. And that’s very true. Writing for DC and Marvel and Star Trek and Men in Black and X-Box was just a blast for an old kid like me. Period, end of discussion. But for some reason I answered a different way with this interviewer. I answered, “Practice.” You see, for every media book I wrote, I focused on one thing to practice for that book. For example, on three novels in a row, I worked on nothing but different forms of cliffhangers. The reviews on those three books for the first time in my career started adding in the phrase “hard to put down.” Focused practice, then feedback, then more focused practice, then more feedback. That’s the loop you want to try to set up in every way possible.

How else can you practice technique in the craft of writing?

Copy great works by hand.

This is how Benjamin Franklin taught himself to become a powerful writer.

Jack London too, in lieu of any traditional education.

Oh, and Hunter S. Thompson copied The Great Gatsby and A Farewell to Arms while working at Time Magazine.

When the author of classics like Treasure Island and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde decided he wanted to learn how to really write, he copied word for word the great prose of those who had come before him. Stevenson would take a passage from a great writer and carefully read it twice. He’d then turn over the passage and try to reproduce it from memory — word for word and punctuation mark for punctuation mark. At first the exercise was a tremendous struggle and his attempted copies were riddled with errors. But with practice, he was able to read huge passages and reproduce them from memory with exactitude. He continued the practice even after he became a literary success. Besides helping him learn style and grammar, the way Stevenson did his copywork — reading the passage twice and trying to replicate it from memory — also made him a more attentive reader. Which, of course, only helped further improve his writing. G.K. Chesterton would say that Stevenson always seemed to have an uncanny ability “to pick the right word up on the point of his pen.” The irony is that Stevenson’s originality and sharp eye for style was forged from years of studied imitation.

In fact, more writers than you’d be able to list first cut their teeth on deliberate studied imitation.

You could set aside a portion of writing practice time each week where you’re just going to copy out the works of authors you admire by hand.

Grab a notebook, a copy of a work you admire, and a beverage and get to work feeling the rhythm of a master wordsmith flowing through your pen.

And, please, do this by hand.

I’m with Ryan Holiday on this one when he talks about keeping a commonplace book by hand:

Technology is great, don’t get me wrong. But some things should take effort. Personally, I’d much rather adhere to the system that worked for guys like Thomas Jefferson than some cloud-based shortcut.

And while you’re at it, keep a notebook where you collect quotes, cool lines from books, or different writing techniques.

I recently read Ludlum’s The Bourne Identity, and I was able to learn a lot about cliffhangers by copying out how Ludlum ends his chapters.

This leads to the next critical part of deliberate writing practice.

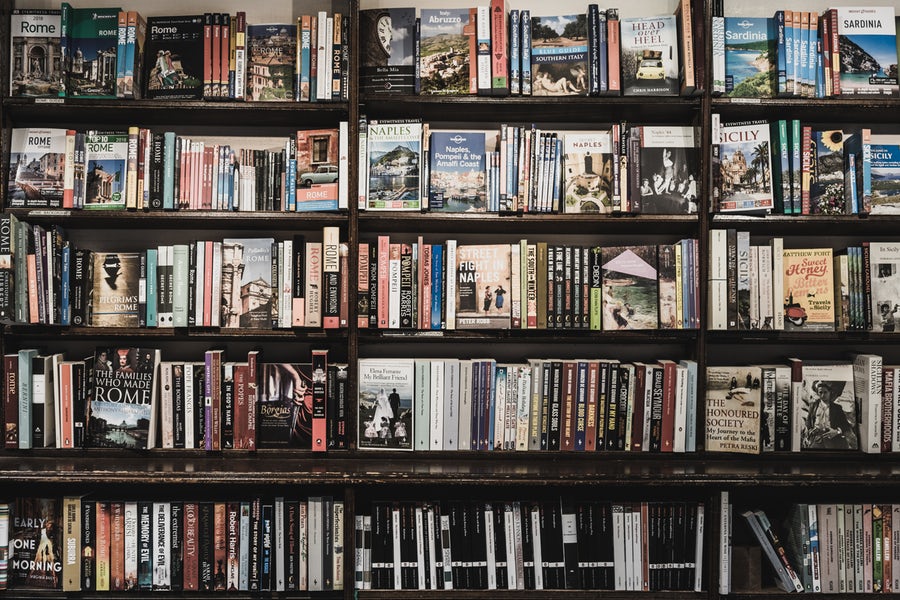

Deliberate reading.

You can’t learn to write in a vacuum.

- Every great musician is first and foremost a fan of music.

- Every great football player is an admirer of the sport.

- Every great writer is a reader first.

You need to immerse yourself in writing.

Read fast, for joy, for pleasure, and you’ll learn by osmosis.

But every so often you’re going to want to hone in on what you’re reading.

When you find a part of a book that really strikes you, slow down.

Read it slowly, read it again and again, break it down and figure out how the author put it all together.

And sometimes you’re going to want to read fiction with an aim to learn a specific technique that you can apply in your own writing.

Nicholas Sparks, of The Notebook fame, talks about how he reads over a hundred books a year and every single book teaches him something:

- Stephen King’s The Shining can teach you how to be scary

- John Grisham’s The Firm can teach you how to build suspense

- Christopher Moore’s Bloodsucking Fiends can teach you humour

- Tom Clancy’s The Sum of All Fears can teach you multiple plot lines

Sparks also advises to focus in on the specific genre you want to write in and DEVOUR books in that genre.

Focus in on the genre you want to write, and read books in that genre. A LOT of books by a variety of authors. And read with questions in your mind. In a thriller, for instance, you might ask: how many characters were there? Too many or too few? How long was the novel? How many chapters were there? Was that too few, too many or just right? How did the author build suspense? Did the author come out of nowhere with a surprise? Or did the author drop hints earlier? If so, how many hints? Where in the novel did he put them? Was the suspenseful scene primarily narrative or dialogue? Or a combination of both? Did that work? Would it have been better another way? Where did the bad guys come in? In the beginning? The middle? When did they first meet the good guy? What happened? Did the reader know they were bad? Did they do something bad right off, or was it something that seemed good at the time? Then, read another thriller and ask yourself those questions again. Then read another and another and another and ask those same questions. And keep reading your entire life and asking questions. Little by little, you’ll learn the process.

It’s an iterative process.

Read, question, answer, learn, apply.

Read, read, read.

And read some more.

As Bradbury might say: “live in the library”.

Practice in writing is all about humbling yourself and committing to the craft.

Don’t approach the next year of your writing life as the year you’re going to “make it big”.

Approach the next year as your apprentice year.

Brandon Sanderson, author of the fantastic Mistborn series, talks about his apprentice years:

This all started in earnest when I was 21, about eleven years ago, back in 1997. That was the year when I decided for certain that I wanted to write novels for a living. My first goal was to learn to write on a professional level. I had heard that a person’s first few books are usually pretty bad, and so I decided to just spend a few years writing and practicing. I wanted time to work on my prose without having to worry about publishing. You might call this my “apprentice era.” Between 97 and 99 I wrote five novels, none of them very good. But being good wasn’t the point. I experimented a lot, writing a variety of genres.

College athletes have a redshirt year.

This is essentially a throw-away year where your only concern is getting good enough at all the different components of your sport so you can have a shot at the bigger leagues.

You do drills, build your body, and put in relentless amounts of practice time.

So when the time comes, you’re ready.

If three apprentice years were good enough for someone like Sanderson (and you could argue his practice years actually extended at least well over a decade), then you can put your dreams of hitting it big on hold for the next year and spend that time wailing on your craft.

A Deliberate Practice Schedule For Writers

I can’t tell you what your deliberate practice schedule should look like.

But I can give you some rules of thumb that might help you build your own.

1 – BE WORKING ON SOMETHING. Preferably several somethings. A novel. Short stories. A screenplay. Poems. Articles. Have a work-in-progress that you’re excited about, but have some other things you can turn to when you need a change of pace or mood.

2 – WRITE EVERY DAY WITHOUT FAIL. Make a commitment and keep to it. Start with a time amount and increase it when you can. This needs to be every day and you need to be religious about it. Devote yourself to daily practice.

3 – GO INTO YOUR WRITING SESSIONS WITH AN AIM. Maybe you’re going to focus on creating suspense or crafting compelling dialogue or weaving multiple plot points together. Doesn’t matter what it is as long as you know what it is.

4 – READ VORACIOUSLY AND DELIBERATELY. Read every single day. In a perfect world, this would look like a 50/50 split between writing and reading. Write one hour, read one hour. But life’s not like that. Some days you’ll be able to read several hours in a row, while some you’ll just have your morning commute. Snatch every chance you can. Read in your genre and outside your genre. Study how other writers do it. Study craft books and take courses like MasterClass and The Great Courses too.

5 – PRACTICE DELIBERATELY. In addition to your work-in-progress, set aside time to isolate different parts of the craft and practice just for the pure fun of it. Writing exercises like this one recommended by Brandon Sanderson, practicing writing cool book titles, or copying out the works of great authors by hand – all of this is valuable and necessary.

6 – GET FEEDBACK. Share your work with the world. Share with friends, fellow writers. Find beta-readers. Collect rejection letters from publishing houses. Pay attention to your critics and reviews.

So what are you waiting for?

Get practicing.

Get reading.

Get writing.